Researcher Anders Persson clicks around in his inbox and reads aloud from one of the emails.

“I wish neither you nor your family well. Perhaps you will suffer the same fate as all the innocent people in Gaza.

“Have nice day, you filthy Nazi!”

He received this one in late May 2024, when protest camps had been set up on several campuses in Sweden, including at Linnaeus University. People were protesting against the war between the terrorist group Hamas and Israel, and they wanted the universities to take a stand against Israel.

A few weeks before that email arrived, Persson received a phone call from someone asking detailed questions about the department’s collaborations with Israeli universities and researchers. At the time, there were no such collaborations.

One Sunday evening, soon after the phone call, a colleague of his was sitting in his office working. Noises in the corridor caused them to look outside. A quartet of masked people were moving around outside Persson’s room. They were taking their time, and the colleague was frightened and hid.

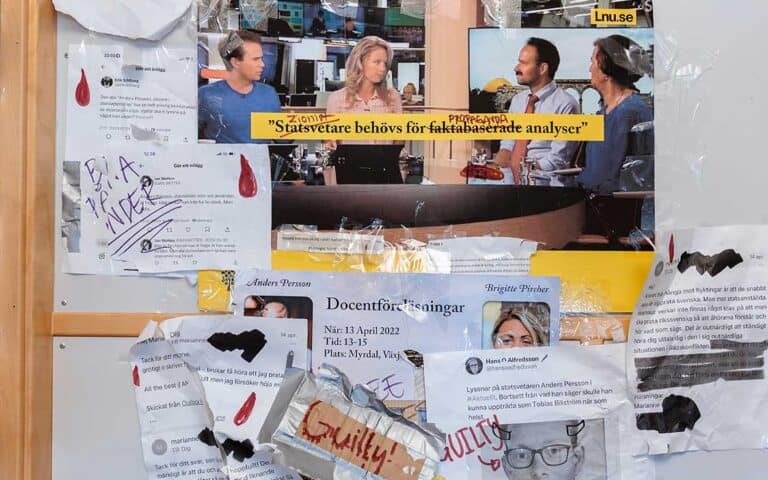

When he arrived at work on Monday, Persson was greeted by a wall on which were pinned children’s clothes splashed with red paint. Messages had been taped up there saying things like “blood on your hands” and “guilty”. An advertising poster for Linnaeus University showing Persson being interviewed in a news studio now had a Hitler moustache drawn on it, and the words “political scientist” had been scrawled over with the word “Zionist”.

Persson underlines that he is not a professional criminal investigator, but he felt that the phone call was part of an information-gathering exercise, and the same thing had happened before.

“I have no idea if the two events were connected, but it wouldn’t be illogical to believe so.”

The children’s clothes have now been removed. Police investigators took them, along some other evidence, but the rest of it still there. he does not expect anyone to be held accountable for what happened.

“The Swedish Security Service was called in, and they contacted me again a few months later to say that no progress had been made. Since then I’ve heard nothing.”

Anders Persson conducts research on the conflict between Israel and Palestine. He teaches international politics and appears in the media as a Middle East expert. This was not the first time he had been subjected to threats, hatred or harassment. Angry emails, debate posts and comments on social media are the most common forms.

A study by the University of Gothenburg (read more) shows that four out of ten researchers and university teachers have been subjected to threats, hatred or harassment. Although Persson’s case is one of the most high-profile in recent times, he feels that he is not one of those most at risk.

“If your name is Anders Persson and you’re from Landskrona, like me, it’s very difficult for someone to label you a traitor and claim that you’re an agent of a foreign power. If my name had been Mohammed or Moshe and I’d had Jewish or Arab ancestry, it would have been a hundred times worse. If not a thousand.”

According to the study, it is also more common for women to be victims of this kind of behaviour, as Persson points out. Had he been a woman, he believes he would have suffered more hatred and worse threats.

“When I am criticised and attacked, there is no sexual element. No-one wants to rape me, and no-one wants to have sex with me.”

Since the incident at his office, things have been calmer, he feels. The protest camps have disappeared and there is now a ceasefire in place in Gaza, albeit a fragile one. Things have been almost too calm, which is why he asked the university’s security department to conduct a security assessment.

“Since Trump won the election, he has also stirred things up quite a bit with Gaza, so it looks like we are in for four turbulent years.”

Persson was recently given a personal alarm, and other security measures for him are currently being assessed. The door to his department is unlocked during office hours, and this has been discussed from time to time. The question is whether locking it would solve much, he says. For example, it should not be unlocked on Sunday evenings.

“But for some reason they got in. Either the door wasn’t locked properly or someone let them in. Or someone hung around in the building before it was locked.”

At Karlstad University, researcher and university lecturer Tobias Hübinette walks briskly through the corridors. He stops at a locked glass door and takes out a card holder.

“This is where the problems start, and it’s because of me. Because I work here,” he says.

The door to the department where he works is locked 24 hours a day. There is no information on the university’s website about where Hübinette’s office is. This has been the case since the attack in Almedalen in 2022, when Ing-Marie Wieselgren, a psychiatrist and the national coordinator for psychiatric issues at Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, was murdered in broad daylight after a seminar. Hübinette’s name was on the murderer’s list of potential targets.

Actually, it all started earlier than that. Tobias Hübinette has been working in Karlstad since 2015 and conducts research in areas such as racism, migration, minorities and Swedishness. The subjects he teaches include intercultural studies and gender studies.

He has also long been known as a controversial figure in numerous circles. He co-founded the magazine Expo, which categorises itself as anti-racist. In his youth, he was active in the autonomous left. Later, he left his job at Stockholm University after a conflict with some colleagues. Over the years, he has accumulated a number of criminal convictions.

On his very first day in Karlstad, he was informed that there had been objections to his employment. He firmly believes that the protests came from the political right.

“They had found out that I was going to start working here, and it has just continued since.”

On the corridors, in cafés and in the library, students might make it obvious that they recognise him, sometimes in ways that he perceives as threatening. People sometimes post where he is or where he has been seen during the day on social media.

The most recent example was when someone posted on social media that he would be in a certain room at a certain time, he says. He thinks it was probably an employee, as it was a seminar that had been advertised internally.

“I’m certainly not implying that there is violence or assault or worse involved. But this kind of harassment happens all the time.”

Perhaps the incident that received most attention in the media took place in 2023. A person who is an active blogger on the political right announced to their followers that they would enrol on one of Hübinette’s courses. Before the course even started, Hübinette filed a complaint of harassment, as he believed that the student would observe and gather information on him and other course participants.

The course was delivered remotely. After the first session, Hübinette took sick leave and a colleague took over. A couple of complaints against the student were dealt with by the university’s disciplinary board. In October 2023, it was decided that the student could continue the course. However, the chair of the disciplinary board, the vice-chancellor of Karlstad University, Jerker Moodysson, disagreed with the decision.

The course in question is still being offered, says Hübinette, but right now it only has one student.

“The course has been sunk, you might say, and that was probably the intention. My theory, and I think this is true, is that people simply don’t dare to take it. Because there is always a risk that if you take my courses or have me as a teacher, you can be observed, exposed or end up on a political register. You could also have your name and picture published on social media.”

He has long been cautious about going out at night in Karlstad. He is recognised every day, he says. This is noticeable as we walk through the lunchtime crowd of students outside his office. Some turn around and his name is whispered several times.

The fact that four out of ten researchers have experienced threats, hatred or harassment is a threat to academic freedom, says Tobias Hübinette. He can understand researchers who are cautious, change specialisation or choose other careers because of a hostile environment. He has not reached that point himself. He continues to teach and research the same subjects as before.

“I believe in what I do. What else would I do? This is what I’m passionate about and what I’m good at, so it would be a major concession to give up.”

Anders Persson in Växjö has a similar opinion. He has not become more cautious as a researcher.

“At the same time, you have to make a new assessment after each threat. I might not have seemed so tough if we had met on another day and I had received a death threat the night before. And if something even more serious happens, I may have to reassess.”

However, hatred and threats affect him on a private level. He doesn’t go out in the evenings and is careful about what he writes on social media and in emails.

“At any time, someone could come up and film me or shove a tape recorder in my face. Or want to put me in a compromising situation somehow,” he says.

Tobias Hübinette describes how the threats against him make research communication difficult. He feels that his work is not recognised by the university in the same way as that of others

“I think it’s because they don’t want to put even more spotlight on Karlstad University. But it may also be out of concern for me,” he says.

Anders Persson has not felt that communication research has suffered. He tells of a short interview the university did with him at the beginning of the war in Gaza, which was shared on the university’s social media channels.

“There was a minor storm of hate where a lot of different people, I don’t know if they were students or not, commented very aggressively. Then the post was removed.”

To some extent, the two researchers have differing views of the employer’s capacity to provide support in situations where people experience threats and hatred. Persson feels that his employer is competent when it comes to security matters. He used to work in Lund, and he felt the same way there, although the threats and hatred towards him were not at the same level back then. He was not as well known, he says.

Hübinette believes that his employer took the incident with the blogger on his course very seriously. But a few years ago, he reported another person for threatening him over the phone, which led to a court case and a conviction.

“I had to deal with that all by myself and didn’t even have people from the university with me at the trial. I sat alone, while the perpetrator had their friends in the courtroom.”

He says that he received no support to prepare for media interviews or in his contacts with police and lawyers, even though the incident was linked to his professional role.

“That is something that I would like to see more of. Help from the employer to deal with the legal system and legal processes.”

Nowadays, Tobias Hübinette rarely has the time or energy to report everything. But he still advises researchers who are subjected to threats, hatred or harassment to be open about it. To both their employer and their colleagues.

“Lawyers, security managers, the IT department and whoever. Inform them all the time about what happens. Tell people. Don’t just sit quietly and deal with all this by yourself.”

Anders Persson agrees.

“It’s important to delegate. If you feel that you are being intimidated, then you should hand the matter over to your immediate superior and to a lawyer so that they can make a professional assessment about how to proceed,” he says.

Proposals on stricter penalties for threats and hatred

The government has proposed that changes to the legislation on violence, threats and harassment against state employees come into force on 2 July 2025.

If the bill is passed by parliament, it will result in stricter penalties for this type of behaviour.