Marine biologist Ellen Schagerström has to struggle to get her diving suit off. Ice-cold Baltic Sea water runs down her cheek. For the past few months, she has been leading the ReCod project, run by the BalticWaters foundation. Its aim is to help the hard-pressed cod stocks in the Baltic Sea to recover.

“I think there is hope. We know that the people, voters, want to protect cod. Now we just need politicians with the courage to make the necessary decisions,” she says.

A fishing ban is already in place, but oxygen-poor water and low salinity are inhibiting the revival. A new laboratory outside Nyköping aims to change that. A system is being built where Baltic Sea water is circulated and resalinated to improve conditions for cod.

“We want the cod to be as healthy as possible, spawn naturally and produce a lot of eggs,” says Schagerström.

The breeding cod will be caught in the Baltic Sea, allowed to recover in the facility and, after reproduction, be released back – healthier than before.

“Just like after a visit to a spa,” Schagerström jokes.

But there are plenty of challenges. Few of the fry released are expected to survive.

“For every thousand cod released, we will be delighted if ten survive. There is so much we don’t know about their early life and development.”

Cod is the most important predator in the Baltic Sea. When cod disappears, small sticklebacks take over.

“They not only eat cod fry. They also keep down the numbers of other species, such as perch, pike, herring and zander. If we get the cod back, it will eat sticklebacks. That benefits the whole ecosystem.”

Cod farming is expensive, and every day in the lab costs money. Schagerström is developing a method to take the fish from the larval stage to about two centimetres in length. That size is crucial – slightly bigger than the width of a stickleback’s mouth. Then the small cod are finally too big to be devoured, at least by a stickleback. That is not to say that the danger is over; once out there, other voracious foes await, such as cormorants, and not least the harsh Baltic environment.

“The foundation’s breeding facility is a demonstration project, to show that it is possible to breed and release cod,” she explains. “We can make additional releases, but that is not what will turn things around. The Baltic must be given a chance to recover. When that happens, we can speed up the process.”

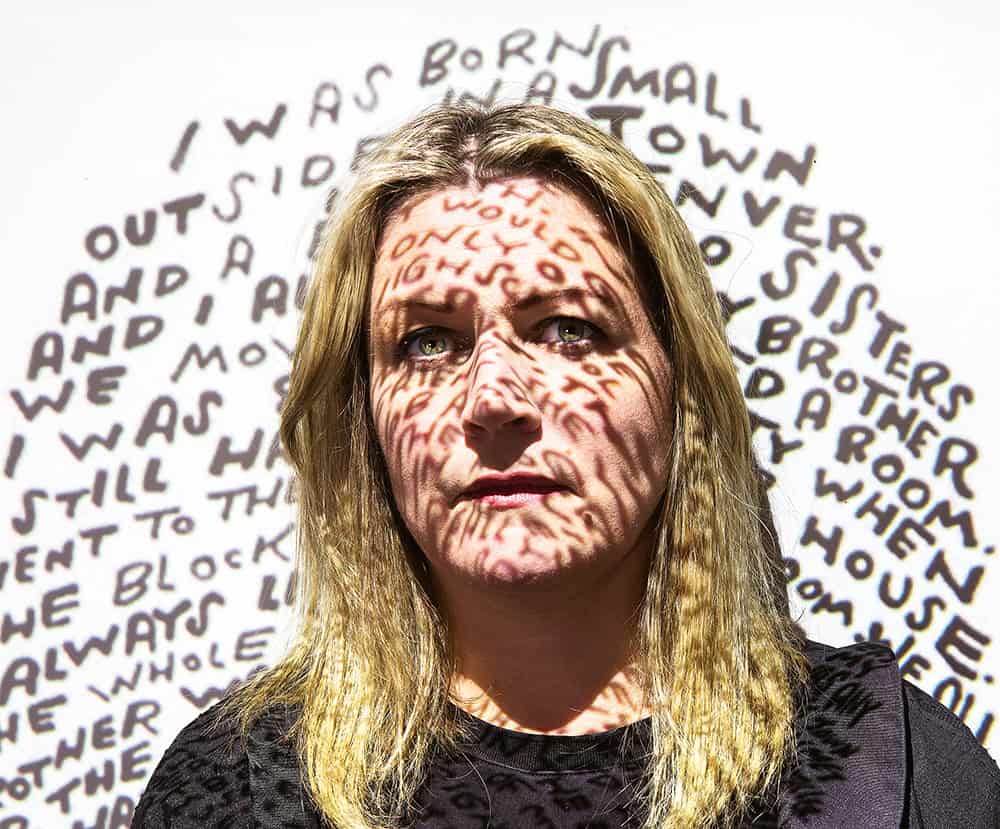

Ellen Schagerström has an unusually strong popular education pathos and tries to find new ways to communicate her research. She sees no mystery in the fact that not everyone listens to researchers – not when research is communicated in a boring and inaccessible way. At lengthy conferences, even she, a researcher herself, has sometimes taken out her phone and started playing a game to pass the time.

She calls herself a seaweed influencer and runs a seaweed blog (Tångbloggen) and an algae podcast (Algpodden), which have a broad audience, ranging from pre-school classes to people working at county administrative boards and municipalities. She uses them to raise awareness and spread knowledge about algae.

“The blog is aimed at the general public. The podcast, which is in its fourth season, is at serious geek level. We recommend it for people with insomnia,” she laughs. She runs the podcast together with a former colleague, Angela Wulff, a professor of marine ecology at the University of Gothenburg.

Schagerström has a particular memory of a British person on holiday in Sweden who asked the seaweed blog a question about algae. This led to a long exchange of emails about various aquatic plants.

“The best holiday I’ve ever had,” he wrote when he returned home. He bought a book about algae and went to the English coast to learn all about them.

“It was so cool to take someone from zero knowledge to a passionate interest,” she says with a smile.

She got the job at BalticWaters after appearing on stage. She had a self-written stand-up routine about marine issues, performing at such places as the Norra Brunn comedy club in Stockholm. It was funded by the foundation. The idea was to reach out to people about difficult environmental issues in a new way, to sow a small seed of awareness that could then grow.

“What we laugh at most is actually what scares us,” she says. “If you can laugh, you can listen. It gives you a positive feeling in your body instead of anxiety.”

Studying improvisational theatre at Goldsmiths University in London as a young au pair gave her the tools for performing, along with a crash course in stand-up. It may be a laugh, but Schagerström takes it seriously. She believes that reaching out to people is not just a hobby; it is a duty.

“We researchers live off taxpayers’ money. People have a right to know what we do and to feel that our research is there for them.”

At the same time, she talks about the long working days of a researcher and the communication that is demanded, and that these do not result in higher salaries or a noticeable boost to their careers. She thinks that communication efforts should be given more weight in calls for proposals.

Not all her colleagues have appreciated Ellen Schagerström’s extrovert nature, but she has never felt vulnerable about performing and speaking in public. Perhaps that has something to do with the subject.

“It would have been different if I was working with seals and cormorants,” she says. “Grumpy old men don’t care about kelp.”

And in spite of everything, her stand-up received strong support from colleagues. In Gothenburg, the audience was full of biologists, and the biggest laugh of the evening came when she talked about seaweed.

“The other comedians were not prepared for that,” she laughs.

Her childhood on the island of Visingsö in Lake Vättern was characterised by water and freedom. She describes herself as a “natural case” – it was obvious that she would work with biology. Her curiosity grew among the flowers in the ditch outside her house, and during a visit to the Gullmaren fjord on the west coast of Sweden with her upper secondary school class, she realised that the sea was the place for her.

“I saw a sea urchin. It was absolutely fantastic, and then I just knew then that I would be a marine biologist.”

Since then, the Gullmaren fjord has played a recurring role in Schagerström’s life. As a researcher at the University of Gothenburg, she researched aquaculture, marine restoration and spiny sea cucumbers. The cucumbers, which are closely related to sea urchins, are particularly close to her heart since a thesis project in the Philippines in the early 2000s, where she studied the breeding of Asian varieties. These echinoderms are endangered, as they often get caught in bottom trawling. Schagerström was the first person in Sweden to successfully get our Swedish red cucumber to reproduce in captivity. Cucumbers will continue to be her passion, and she may visit them in the summer when she goes diving, but right now she does not have the time. Last summer, the breeding animals were released into Gullmaren, where they were once common. But she had no hesitation in taking the new job at BalticWaters when the offer came.

“The money for the sea cucumbers was due to run out in a year or two. You can’t chase the rainbow all the time,” she says.

For now, she still has one foot in academia, in a project she refuses to let go. At the end of last year, live bladderwrack were launched into space for a few minutes. The brains behind this were Schagerström and her former supervisor, Professor Emeritus Lena Kautsky, who is a legend in algae circles and known as Auntie Seaweed. It was the first time living macroalgae were studied in space. They are now waiting for the results and hoping for another seaweed journey – this time to the International Space Station (ISS). Ultimately, they want to solve the mystery of seaweed reproduction.

Ellen Schagerström has never dreamed of an academic career, however, and she does not think she will return to it full-time. “In Sweden, it is difficult to move between academia and what we might call the real world. There is no movement back and forth. That is a pity. Academia would gain a lot by making it easier to for people test knowledge in practice and then return with new questions.”

One of the obstacles, she says, is the pressure to publish. After a certain period of time, results need to have been achieved, and those who do other things fall behind. At the same time, she seems to have found a way to do both at BalticWaters.

“I will continue to conduct scientific, publishable research on cod. And I still have my international sea cucumber network,” she says.

The cod farm will be completed this summer, and the first fish will move in in November if all goes according to plan. She still spends a lot of time applying for funding, which is reminiscent of her life as a researcher, but the working days are more regular now, the pace slower.

“Research is great fun in a way that can easily lead to addiction. I want more time for friends and less work pressure,” she explains.

This multi-talented multi-tasker should have no problem filling her spare time. She has a keen interest in food, and Ordfront Publishing will soon publish her first cookery book – about invasive oysters. Perhaps there will eventually be an algae recipe book too. That remains to be seen, but as something of a connoisseur, she is trying to find a language for the flavours of the algae she likes to use in her cooking: different types of saltiness, burnt rubber, ulva intestinalis that tastes like truffles but not as nauseatingly perfumy, and so on.

Ellen Schagerström’s work

Ellen Schagerström is a project manager at the BalticWaters foundation, where she is leading a demonstration project to save Baltic cod. Her PhD was in plant ecology at Stockholm University, where she studied the controversial brown macroalgae Fucus radicans, which is endemic to the Baltic Sea. After her PhD, she remained at the Department of Ecology, Environment and Botany, working with environmental monitoring. She then continued as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Gothenburg, studying the red sea cucumber and its potential role in aquaculture. An ongoing, long-standing side job as a freelance tour guide has taken her to places such as Madagascar.

Her career has not been straightforward, but Ellen Schagerström is playing the long game, and her dream is clear: to one day restore the almost thirty-kilometre long Gullmaren fjord, which has been so important in her life. The fjord, with its Old Norse name meaning God’s Sea, is a marine reserve with a long tradition of research, but it suffers from eutrophication, invasive species and chemical pollution.

“It needs some defibrillation. A large-scale project where everyone around the fjord works together with major measures for all the different ecological functions.”

There she would be able to us all the knowledge she has acquired. Sea cucumbers are known as the vacuum cleaners of the sea and, together with mussels, they can cleanse both the seabed and the water of excess nutrients. Algae are needed, and top predators such as cod need to return. She sees the foundation approach as a key: less bureaucracy, more action. Gullmaren fjord was on her mind when she accepted the job at BalticWaters.

“I really enjoy the scientific approach. But what I’m really passionate about is repairing and restoring nature to better health. To take the research and make it work. And you have a lot of fun in the meantime, together with a group of people who are all good at what they do. That’s the whole point. Why spend time being bored?”

About Ellen Schagerström

Ellen Schagerström plays the violin, preferably folk music together with her father. In her garden at home in Stockholm and in the countryside in Lysekil, she grows wildflowers, such as different white anemones. She practises sniping and scuba diving – preferably close to the surface. She is currently founding the Swedish Algae Society, to promote knowledge of algae. Her favourite alga is Gephyrocapsa huxleyi, a photosynthesising plankton species that drifts around the world’s oceans.