On 5 December 2023, around a hundred researchers and university teachers gathered at the green gates of the Universidade do Algarve in the town of Faro in southern Portugal. José Moreira, president of the higher education trade union Sindicato Nacional do Ensino Superior, Snesup, shows how the protesters marched across the campus and up to a rectangular yellow and white building which has one side adorned with a large seahorse made of rubbish.

He was one of the speakers, along with representatives of other unions and organisations.

“It is outrageous and completely unacceptable that 90 per cent of researchers have precarious employment,” says Moreira. “We are angry about the situation. At the same time, it was good for us to gather at the demonstration, meet our colleagues and discuss shared problems.”

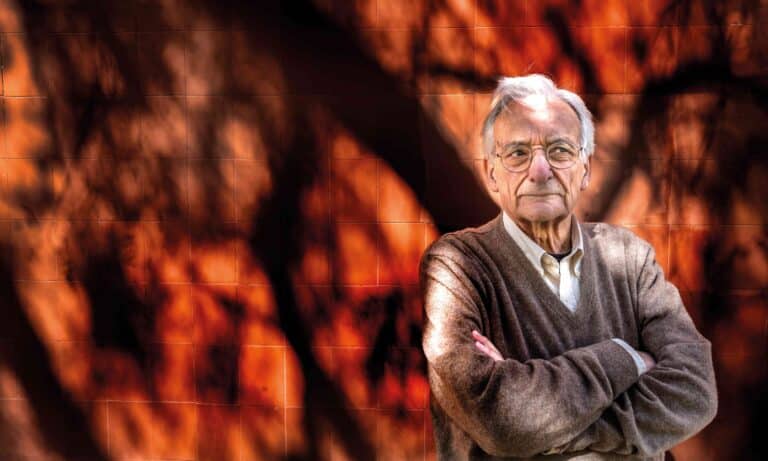

A short distance away is the Faculty of Science and Technology. José Moreira works there as professor auxiliar, the first of the three teaching levels in Portugal, and is a Doctor of Chemistry.

Employees with insecure jobs also see their salaries stagnate, he explains.

“Their salaries are at the same levels as two decades ago. We have people who are retiring now whose pension is less than the minimum wage.”

Living with precarious employment is tough, Moreira continues. It is hard to start a family if you do not know if you will have a salary in a year or two. Scholarships and similar types of income only give the right to the minimum level of social security and it is difficult to get a bank loan to buy a home.

Some researchers move abroad to survive.

“Many suffer from anxiety and other psychological problems. We try to talk with them. They need to be listened to in order not to feel alone.”

Moreira says that precarious employment is above all a consequence of the financial crisis of 2008, which hit Portugal hard. In 2017, the government of the day launched a programme against precarious employment in the public sector, but it has completely failed when it comes to researchers, he feels.

“We protested outside the vice-chancellor’s office every week for several months in order to get researchers integrated into the regular workforce.” Then came the programme specifically aimed at researchers that would turn scholarships into three-year contracts.

“It was a first step, but we were not satisfied because it was about short-term contracts and only applied to state-run universities. The salaries were also far too low – two-thirds of a normal researcher’s salary.

In 2023, the government initiated the FCT Tenure Programme to create 1,400 permanent positions for researchers and teachers by the end of 2025. The idea is that the programme will be repeated every two years.

“It is the first time we have had such a programme, and it is good, but there are too few places. We estimate that there are between 5,000 and 6,000 researchers with precarious employment.”

There is also a problem with ‘guest teachers’, Moreira continues. In Portugal, there are around 31,000 state-employed university teachers and over 40 per cent of them are guest teachers.

“About half are fake guest teachers. They are not really guests. They have no other occupation on a daily basis. They teach in the same way as we other teachers do. But they have more lectures and earn significantly less than we do.”

Employed teachers, he continues, have a maximum of nine lecture hours per week. The guest teachers have anywhere from 14 to 20 hours. Moreira, who has worked at the Universidade do Algarve for 25 years, has a net monthly salary of 2,400 euros, around SEK 27,000. A guest teachers’ net salary is 1,000 to 1,200 euros.

“There are people who have worked under these conditions for 20 years. Among private universities, the number of people in precarious employment is even higher.”

Portugal is still one of Western Europe’s poorest countries, but at the same time has Europe’s third fastest growing economy.

That economic growth, however, is not something that the employees within the higher education sector have noticed, says Moreira.

“Low salaries are our biggest problem. In the past 20 years, those of us who work in higher education have lost a third of our purchasing power. We believe that there is scope to increase pay.”

The union’s demands are listed in the manifesto that hangs on the office door. The most important priority is to put in place a new programme for permanent employment for both researchers and teachers.

“Things have started to happen, but progress is very, very slow.”

The situation is currently unclear. In December last year, the Portuguese government fell after allegations of corruption andon the 10th of March, after Universitetslärarens interview, elections were held.

“What happens now depends entirely on which government we get,” says José Moreira.