When the most recent Research Bill was presented in 2021, it committed almost SEK 14 billion to research over three years. In a letter dated 26 April this year, Minister for Education Mats Persson invited Swedish universities and colleges to provide input ahead of the government’s work on the next Bill, which is due to be presented next autumn. Now the referral period has come to an end, it is clear what is at the top of the higher education institutions’ wish lists regarding the Bill: Money.

Yes, when the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions (SUHF) summarises its recommendation regarding the Bill in seven points, five of them are about money. The amount of money that the government invests in research needs to increase to 1.2 per cent of GDP, basic grants need to rise and co-financing needs to be scrapped once and for all, the Association writes. It goes on to describe how the long-term funding of research infrastructure needs to be reinforced and emphasises that compensation levels must be raised for all areas of education.

Most representatives of higher education institutions interviewed by Universitetsläraren agree that more money is needed if Sweden is to become the leading research nation that the government aspires to. Only a small number of the 34 referral responses that universities and colleges have submitted do not write explicitly that the basic grants need to be bigger.

Carina Mallard, pro-vice-chancellor with responsibility for research at Gothenburg University, is one of several who describe how basic grants are being eroded as a result of requirements for co-financing. “It would be very important to have a long-term perspective and to be able to have control over our research funding in relation to external grants,” she says.

The problem of erosion of grants is not entirely new, the institutions write in their referral responses. Mallard believes that requirements for co-financing from both state and external funders mean that the institutions are being steered, at least to some extent. “If we had a larger basic grant, we would see more excellent research coming from within the university,” she says.

“If we had a larger basic grant, we would see more excellent research coming from within the university.”

Carina Mallard

Kristianstad University paints a picture in its referral response of how the basic grants have decreased in relative terms over a long period of time. It emphasises that there is a great difference in Sweden between the share of basic grants and the share of government research funds for which institutions need to compete compared with other prominent research nations, such as Switzerland, Denmark and the Netherlands.

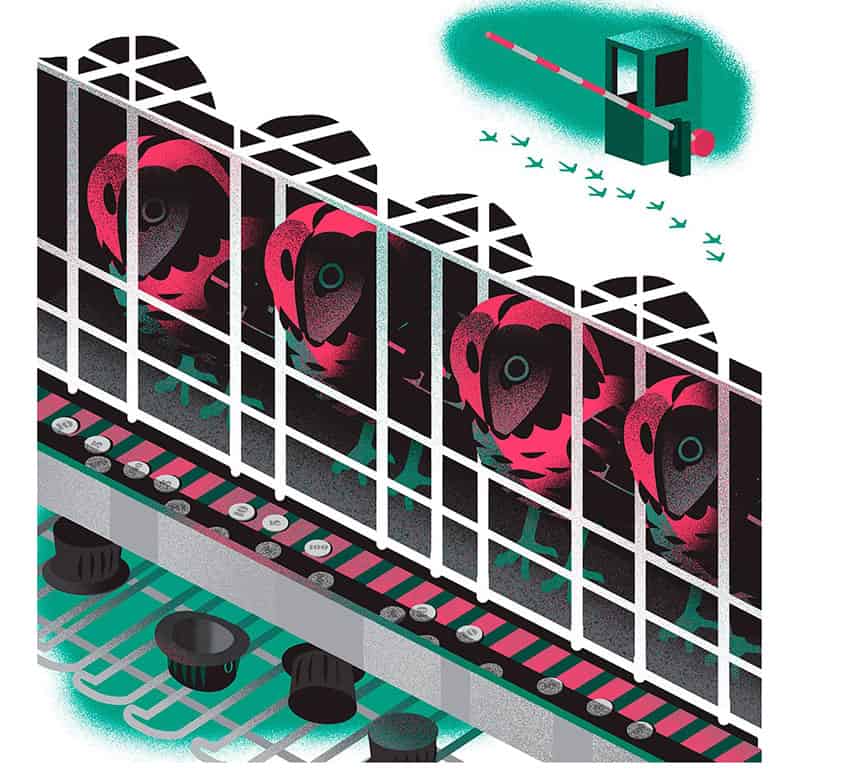

“We need to break a rather one-sided trend where bodies such as the Swedish Research Council, Vinnova, Formas and Forte have been getting more and more of the cake when it comes to investing in research and innovation,” says Tobias Grahn, a business controller at Kristianstad University.

In the previous-but-one Research Bill, presented in 2016, just over half of the funding was allocated to state research councils. The corresponding share in the most recent Bill was 75 per cent, the university writes in its response. As the higher education institutions’ dependence on external funding grows, the strategic decisions are being shifted slowly but surely to the research councils, says Grahn. With shrinking resources, it is also more difficult for universities to create long-term conditions for secure employment. “Furthermore, it is a rather expensive and inefficient system if our researchers have to spend so much time applying for funding.”

The Royal Institute of Technology, KTH, also calls for a change in the balance between basic funding and external funding. This can occur either through a substantial increase in the former or through a redistribution of funds from the state research financiers,” KTH writes.

“We see that the balance is getting worse and worse. It is also accentuated by the fact that the more external grants we receive, the more of the basic grants go to co-funding. That in turn means that we cannot build up the faculty in the way we would like,” says Annika Borgenstam, deputy vice-chancellor for research at KTH. She would prefer to see state funders pay for research projects in full and the requirement for co-financing be removed.

“The more external grants we receive, the more of the basic grants go to co-funding. That in turn means that we cannot build up the faculty in the way we would like,”

Annika Borgenstam

Another higher education institution that emphasises that a larger share of the available resources needs to go to higher education institutions is Södertörn University. ”Increased basic funding is essential in order to be able to work long-term and achieve excellence and both national and international research impact”, the university writes in its referral response. Basic research and long-term collaborations are disadvantaged by an excessively large external funding component. In addition, ”the need for immediate research about individual events, as well as intellectual risk-taking” is affected.

What the balance between basic grants and external funding should be has not been discussed in detail, according to Anna Maria Jönsson, deputy vice-chancellor for research at Södertörn University. “But why not at least follow the examples of strong research countries like Denmark and the Netherlands?” she says. “There the balance is slightly reversed compared with here, and the universities have a larger share of basic grants than external grants.”

So there is a broad consensus among Swedish universities and colleges regarding the need for more money and that they would like to be able to have more freedom to decide how to use their money. But they also agree on other areas that need to be strengthened if Sweden is to be able to become the prominent research nation that the government is aiming for.

Academic freedom, for example. When the currently applicable Research Bill was presented, the government at the time emphasised that the state’s role is to ”safeguard and promote” academic freedom. It also stated that the higher education institutions’ ”independence” had already been strengthened through a number of reforms over the years and that they already had ”broad scope to decide for themselves how their activities should be organised and how resources should be used”. However, in the referral responses regarding the upcoming Bill – and in interviews with Universitetsläraren – a number of higher education institutions say that full constitutional protection for academic freedom is essential.

SUHF writes that ”political trends, interest groups and troll factories cannot be allowed to govern what may be researched or taught”.

Hans Adolfsson, the chair of SUHF, says that institutional autonomy and academic freedom are vital for universities and colleges to be able to conduct their activities in a credible manner and with a high level of quality. “But as well as the need for increased academic freedom, we are also prepared to take our academic responsibility,” he says.

In their referral responses, most higher education institutions link academic freedom and autonomy to the previously mentioned need for more money. Anders Stenström, head of research and innovation at the University of Borås, says that more substantial basic grants would lead to stronger existing research environments and improved scope to find tomorrow’s environments. “We may not always know exactly what those environments are yet, and that is something that we do not think we should try to influence from our position. For us, autonomy and academic freedom go hand in hand. It is the institutions that are best placed to assess where the money should be invested to develop excellent environments,” he says.

An imbalance between external funding and basic grants thus also restricts academic freedom, he points out. “In the previous government’s Research Bill, fairly large investments were made in increased basic grants. But when even more money went to the various research funders, the balance became even more skewed.”

“In the previous government’s Research Bill, fairly large investments were made in increased basic grants. But when even more money went to the various research funders, the balance became even more skewed.”

Anders Stenström

The currently applicable Research Bill, from 2021, contained an increase in basic grants equivalent to SEK 900 million in 2024 terms. In 2021, the increase was SEK 720 million, apart from a temporary grant of half a billion as a result of the corona pandemic. The Swedish Research Council received just over SEK 1 billion per year. At the same time, Vinnova received SEK 545 million, Formas SEK 257 million and Forte SEK 105 million per year until 2024.

In a report from Studieförbundet Näringsliv och Samhälle, SNS, which came out earlier this year, the report’s author, Roger Svensson, a docent in economics, states that the targeted investments of these four government research funders have increased over time. The share of open research funding was 29 per cent in 2021 and 46 per cent in 2005, according to the report.

Muriel Beser Hugosson, vice-chancellor at the University of Skövde, says that smaller higher education institutions may experience problems. “If a lot of research funding goes through research funders, it is the funders who set the agenda. They decide which areas, but also which research projects, receive funding. That deprives the institutions of the ability to direct their own research. Instead, they are forced to focus on what is popular to research at the time,” she says.

The requirements that higher education institutions must be involved in co-financing external grants mean that the smaller universities and colleges are also often doubly penalised, as she puts it. “The small higher education institutions that receive much less research funding than the large ones can end up in the situation where they have to turn down new research funds because they cannot co-finance, even if they have an incredibly excellent research programme. That will limit their capacity to grow.”

With regard to autonomy, there is one issue on which the state-sector universities are not in quite as much agreement in their thoughts on the upcoming Bill, and that is how they should be organised. Linköping University writes in its referral response that it wants to look at whether the ”current organisational form” is suitable to ensure ”increased independence” and at the same time review universities’ and colleges’ scope to govern how their assets and resources are used.

Uppsala University discusses how higher education institutions are subject to the same regulations as other state agencies, where the latter are largely concerned with the exercise of authority, pointing out that higher education institutions have different conditions and goals, but ”are governed in the same way”.

Another institution that brings up the organisational form in its response is the Royal College of Music, KMH, which would like to see an investigation into a ”new form of organisation for the state-sector higher education institutions”.

“The role of a state agency involves a lot of things that do not benefit our activities and therefore do not benefit the students in the end. Personally, even though it is not in our referral response, I think another form of authority should be created,” says Kersti Hedqvist, director of KMH.

“The role of a state agency involves a lot of things that do not benefit our activities and therefore do not benefit the students in the end. Personally, even though it is not in our referral response, I think another form of authority should be created,”

Kersti Hedqvist

Three years ago, the focus was on freedom, the future, knowledge and innovation when the government of the time presented its Bill. In the coming three-year period, excellence, innovation and internationalisation are at the top of the agenda.

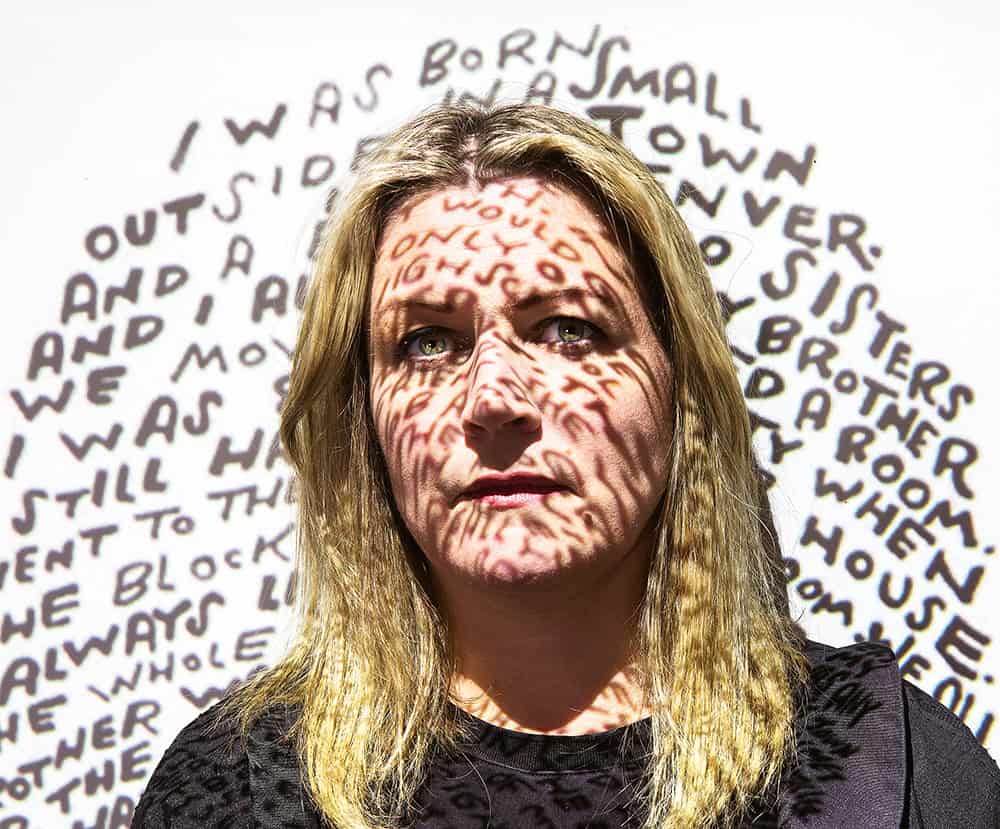

Regarding the latter, higher education institutions are pretty much in agreement on at least one thing: A review of migration legislation is needed to make Sweden an attractive country for researchers, doctoral candidates and students.

SUHF puts it succinctly, writing that it must be made easier to get a residence permit in Sweden.

Jönköping University writes that the aim is to compete on a ”global market”, in both education and research. ”A basic prerequisite for continuing this work is that it should be easy to receive students, doctoral candidates and researchers from other countries,” the university writes in its referral response.

Other universities bring up long processing times and stricter requirements in migration legislation as obstacles to international collaborations and exchanges. One of these is Malmö University, which notes that there are problems with ”mobility” for researchers. “The European dimension is important to us. We want to see good European integration where Swedish higher education institutions have good conditions to work with other European higher education institutions and receive research funds at the European level,” says Josef Chaib, a research officer at the university.

He calls for a policy focused on how Swedish universities and colleges can get better access to research funds through the European Commission and the European Research Council. “These days, it is important to recognise that research is very international and global in nature. We see that some countries are tending to isolate themselves a little, and it is important that Sweden does not do that, so that research does not just become something instrumental for the national role, but that international cooperation is supported and promoted.”

Chaib talks about global issues such as development, international aid, climate and environment, for example. “We describe it as safeguarding the international perspective. The withdrawal of funding for development research is an example of moving in the opposite direction,” he says.

Per Dannetun, adviser to the vice-chancellor on special research issues at Linköping University, believes that a ”single interlocutor” is needed when it comes to internationalisation. It is a problem that the responsibility for internationalisation lies with several different funders, he says. “We do not do very well when it comes to European research in Sweden. Whether that is because we have too much money, because we are too lazy or because we think it’s complicated is a matter that I will leave for others to speculate on.”

A number of higher education institutions also choose to express their views on the funding of long-term research infrastructure, such as the Max IV and ESS facilities. They want to see direct government funding. Dannetun agrees, and brings up the big impact of sudden increases in electricity costs, for example for Max IV last winter.

Several arts universities write in their referral responses about how artistic research is perceived as a low priority. Anna Valtonen, vice-chancellor at Konstfack, the University of Arts, Crafts and Design, points out how Swedish politician talk about STEM, while in other countries they refer to STEAM – science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics. She explains that the arts are not activities for their own sakes, but also integral to social development. Konstfack therefore wants to set up an innovation office. “We are looking for structures to get the artistic perspective into the national regenerative process and into innovative thinking,” she says.

Proper basic research is also important in the arts, she points out. “Without it, it is difficult to see practical applications. In Sweden, there is very little basic research in the arts, and that is something I would like to see change,” says Valtonen.

Johannes Landgren, acting vice-chancellor at the Royal College of Music, believes that research policy needs to include a new perspective on what the arts contribute to a knowledge-building society. “In teaching, research and education policy today, music and all the aesthetic subjects are treated more or less as if it is very nice that people can engage in non-intellectual activities and relax. We believe that music is a knowledge-bearing subject that can contribute to and is an important foundation of knowledge-building in the whole of society,” he says.

“In teaching, research and education policy today, music and all the aesthetic subjects are treated more or less as if it is very nice that people can engage in non-intellectual activities and relax. We believe that music is a knowledge-bearing subject that can contribute.”

Johannes Landgren

Some higher education institutions, including Mälardalen University, believe that the Bill should focus on more than research and innovation. “It would feel better to be allowed to make recommendations on a joint research and education bill. Because higher education and research belong together, which is something I think we agree on in all sorts of other contexts. But you do not see that when it comes to government bills. Education is important for research and research is important for education,” says Paul Pettersson, deputy vice-chancellor at Mälardalen University.

The Research Bill will be presented in autumn 2024. It remains to be seen which of the higher education institutions’ wishes the politicians will grant.

Research funders want billions

In a joint statement, the Swedish Energy Agency, Formas, Forte, the Swedish National Space Agency, the Swedish Research Council and Vinnova write that the research funders’ budget needs to increase by SEK 9.7 billion by 2028.

They want to see measures to make it easier for universities to attract and retain researchers. The funders also write that there is a need for:

-

increased collaboration between society and researchers.

-

a transition to an open science system.

-

a support system for applications, follow-up and evaluation of state-funded research.