Professor Mehdi Ghazinour sits down behind his desk in a spacious room at Södertörn University. Cables are strewn all over the floor. This autumn, the police training programme has moved to brand new premises.

In 2024, he was appointed professor of police science, the first in a subject that is completely new to Sweden. He has his roots in psychiatry, and he became interested in the mental health of police officers through his clinical work with the families of police officers.

“When the police training programme in Umeå, the first outside Stockholm, opened 25 years ago, I applied to work there as a teacher in classes about mental health.”

Mehdi Ghazinour

Professor of police science, Södertörn University

For the past two years, he has been working at the School of Police Studies at Södertörn University. He feels that police research is increasingly becoming a part of the programme.

“The police education teachers who work at the university are interested in and motivated to do research.”

Södertörn University has been running its police education programme since 2015, when the Police Academy in Sörentorp, north of Stockholm, was closed down. Before the Police School, as it was then called, opened its doors in 1970, there was no formal uniform police training programme in Sweden. In the 1980s, there were plans to turn police training into a higher education programme and the school changed its name to the Police Academy (Polishögskolan). But although the programme is now offered at higher education institutions and awards higher education credits, it still does not lead to a bachelor’s degree, even though several government commissions of inquiry have proposed this over the years.

A person who led one of these government inquiries is now the National Police Commissioner. In 2016, Petra Lundh submitted the inquiry report ‘The Police in the future – A police higher education programme’ (SOU: 2016:39). Her inquiry did not assess whether the programme should be an academic education, but what it would look like if it were.

Today, the police education programme is still a commissioned programme, and it gives 120 credits. In order to earn enough credits for a bachelor’s degree, students have to supplement their studies with other courses. Police education is currently offered at five higher education institutions, with a sixth to be added in the near future. Two of the higher education institutions are actively working to offer academic continuation in the form of doctoral programmes within the framework of their police education.

When the police education programme at Södertörn University began, students had to be bussed to different locations for several of the practical elements. On its new premises, there are shooting ranges and other facilities. And in the same way that there is now space for practical aspects of the programme, the university also wants to build in research as a natural part of the educational environment.

Mehdi Ghazinour feels there is not enough commitment to the research component of the programme from the Swedish Police Authority.

“They want research to be a part of the programmes, but they only want to fund the actual education. My ideal situation would be for the authority and the higher education institutions to create a collaborative group together. The Police Authority has 40,000 employees and a number of police officers with doctorates. They should know better,” he says.

Umeå University also now has a professor of police science. It also has the country’s only docent in the subject, Jonas Hansson. He was formerly a police officer and is passionate about bringing research and operational police work closer together.

Umeå was the first higher education institution to offer a master’s programme in police science, and the first doctoral student in the subject, who is now ready to start her PhD studies, actually belongs to Södertörn but will do her doctorate in Umeå.

Hansson hopes that the number of doctoral candidates will soon increase.

“We are now struggling to get funding, and there is very stiff competition for the money.”

Jonas Hansson

Docent of police science, Umeå University

Theoretically strong and established disciplines, such as criminology, are difficult to compete with, he explains.

For research on police work, law enforcement and crime prevention to be taken seriously, and by extension receive more funding, Hansson and others believe that the undergraduate programme needs to lead to a bachelor’s degree. This would require it to be extended, which arouses resistance at a time when efforts are being made to rapidly increase the number of police officers and the Police Authority is struggling with its growth target. Another common argument against an academic police degree is that police officers do not need more theory.

“I interviewed an instructor from Norway today,” says Hansson. “He is a practitioner, but he also has a bachelor’s degree and writes articles about his work. This does not mean that training should be made more theoretical. It is more to do with the fact that there are completely different requirements for an academic first-cycle education. But it would require the entire programme to be reviewed and redesigned to some extent.”

He also believes that it would benefit both research and the police profession if there were higher educational requirements for advancement in the police force.

“Most of us who are police officers and have a doctorate leave the force because our skills are not valued. A bachelor’s degree and advanced-level education build the systems together. If you want to become a specialist nurse, you go back to university to get the necessary competence.”

Several advocates of police education leading to a bachelor’s degree argue that it would strengthen the profession and give it greater legitimacy. But also that it would provide more research that the police could benefit from. The Swedish Police Federation trade union has long been in favour of police training being a university education, and the Swedish Police Authority has not come out against the idea. But there always seem to be other priorities that get in the way.

In a 2021 interview in Polistidningen, the magazine for the Police Federation’s members, the then research coordinator at the Swedish Police Authority, Per Sundström, talked about ongoing work for a comprehensive implementation of research issues in the Authority. This had not been done before and Sundström’s role had just been introduced.

He left the Police Authority in December 2024, and that work has now been taken over by Benny Mälberg, who shares the responsibility with a colleague. In his view, the work of implementing research in the Police Authority is still in its infancy.

“It is an assignment that we are in the process of broadening and developing as part of the authority’s capability development process.”

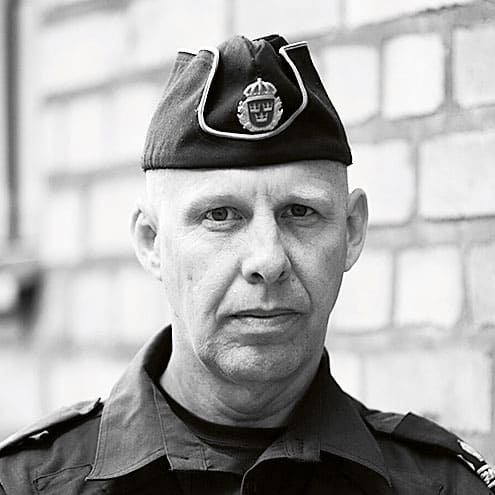

Benny Mälberg

Research coordinator, Swedish Police Authority

Mälberg is not a police officer himself, but has been working for the Police Authority for 18 years. He is positive about the development that is now taking place towards higher education institutions building on police education with master’s programmes and linking research more closely to them through police science.

If there is one thing higher education institutions seem to be looking for in order to attract doctoral candidates, it is research funding. How does the Police Authority view a possible role as a funder of research in police science?

“I cannot give you a good answer to that question now. The authority already funds research, but we need to develop a better way of dealing with the issue of funding. This is something we want to do together with the higher education institutions. I may be able to give you a better answer in a year.”

Docent Jonas Hansson thinks that the Swedish Police Authority’s work on implementing research in its operations and linking up with higher education institutions has been in the starting blocks for too long. His view is that the authority, which is under pressure due to the rise in crime in the country, does not have “time to wait for the research”.

“Here in Umeå, we were commissioned to conduct a scientific study of the Mareld operation, aimed at increasing trust among the local community in Tensta, Rinkeby and Husby, and another on electric shock weapons. Those projects need to be followed up. But that has not happened here. The Norwegian Police Service was interested, on the other hand, so now we are doing it there.”

Police education in neighbouring countries

In Norway, there is only one higher education institution that offers police education, which is in Oslo. The undergraduate programme leads to a bachelor’s degree.

In Finland, police education also leads to a bachelor’s degree.

In Denmark, police education is a higher vocational education programme. It is only offered at one higher education institution. Until 2015, the programme was three years long and led to a bachelor’s degree, but it was then shortened to two years. In 2019, it was extended again by four months.

There may be some cultural resistance to academia, thinks former police officer Hansson. Perhaps especially to the critical approach that is natural for a researcher.

“The police in Sweden have a high level of knowledge, but there is a lot of focus on showing that they have not done anything wrong. But mistakes will always be made. It is inevitable.”

It seems that former colleagues Mehdi Gahzinour at Södertörn and Jonas Hansson in Umeå have slightly different ideas of what police science should be. Gahzinour talks a lot about bringing in experience from other disciplines, while Hansson’s vision is very much about operational research, which is perhaps best carried out by people with personal experience of police work. But if you ask them, the higher education institutions have a close relationship and largely have a common vision for the development of police science research. And now they also have a shared doctoral student. But there is of course a race for research funding going on between them here – both recognise that. And a race to establish their universities quickly as important centres for research.

In addition to Umeå and Södertörn, police education is offered in Malmö, Växjö and Borås. It was recently decided that Uppsala University will also begin to offer the programme. These higher education institutions are also working to implement research in their police education in different ways. In Malmö and Växjö, there is close collaboration with criminology.

They have made varying degrees of progress in developing police science as a separate discipline. In Borås, the ambition is to be able to offer a master’s programme in police science and, in the long term, also doctoral studies. In Malmö, a master’s programme in police work has already been started, as well as a doctoral course in police science for doctoral candidates in other subjects. Linnaeus University in Växjö has a police work programme up to bachelor level.

The police officer, researcher and debater Stefan Holgersson has made a name for himself as being very critical of the Swedish Police Authority, not least its approach to research. However, he has continued working as a police officer in parallel with his research. He now works full-time for the authority as a coordinator for crime prevention work in Police Region East. His view of the Police Authority is that it still has a rather sceptical attitude to research and to the academic world.

“When I was in the maternity ward a few years ago with my newborn baby, I ate in the staff canteen at the hospital. I was struck by how the doctors, the medical staff, sat and talked about research. Their interest in research was so much greater and a natural part of their everyday work.”

This is unusual at coffee breaks in police stations, he says.

“They do not have that tradition. An organisation that is hostile to knowledge in many ways. Not all police officers or police employees, but the organisation as a whole.”

Stefan Holgersson

Coordinator for crime prevention, Police Region East

Now, as a coordinator in crime prevention, Holgersson says that he uses research in his own daily work all the time. And that it is viewed positively by his managers.

“But I am pretty much alone in that.”

How do you view the emergence of a separate academic discipline for police officers, linked to police education?

“I don’t know if I have thought about where police research should be based, but dependence on the Police Authority will be a problem.”

A college or university that runs police education is dependent on a good relationship with the Police Authority, he says.

“The question is whether they would dare to examine the police organisation and its work critically.”

In Norway, where Holgersson previously held a professorship, there is only one higher education institution that offers police education. “So the authority cannot apply pressure by playing higher education institutions off against each other.”

But creating a base for research through the police education programme is something Stefan Holgersson supports.

“I have always been in favour of making the programme an academic education, but not a more theoretical one. I think the programme should be longer, but the students should go out into the field earlier. If you look at medical education, for example, it is very practical, even though it requires a great deal of theoretical knowledge.”

Police Education in Sweden Over Time

1876

A police training program combining theory and practice, with examination requirements, is established in Sweden for the first time.

1977

The Police School opens in Solna, specifically in Sörentorp, just outside Stockholm.

1982

The Police School is renamed the Police Academy, reflecting the ambition to integrate police education into the higher education system.

2000

A police education programme is launched in Umeå. It is the first program located at a university.

2001

A police education programme begins in Växjö.

2015

The Police Academy in Solna closes, and Södertörn University takes over police education in Stockholm.

2016

Current National Police Commissioner Petra Lundh submits the report Police of the Future – Police Education as Higher Education (SOU 2016:39) to the government.

2018

A police education programme starts at the University of Borås.

2019

A police education programme begins at Malmö University.

2024

Mehdi Ghazinour at Södertörn University becomes the first professor in police science. In Umeå, Jonas Hansson, a former police officer, becomes the first associate professor in the field.

2025

Umeå appoints a professor in police science. The first doctoral student in police science begins their research education.

2027

Another institution is expected to offer police education when Uppsala University is projected to launch its program.