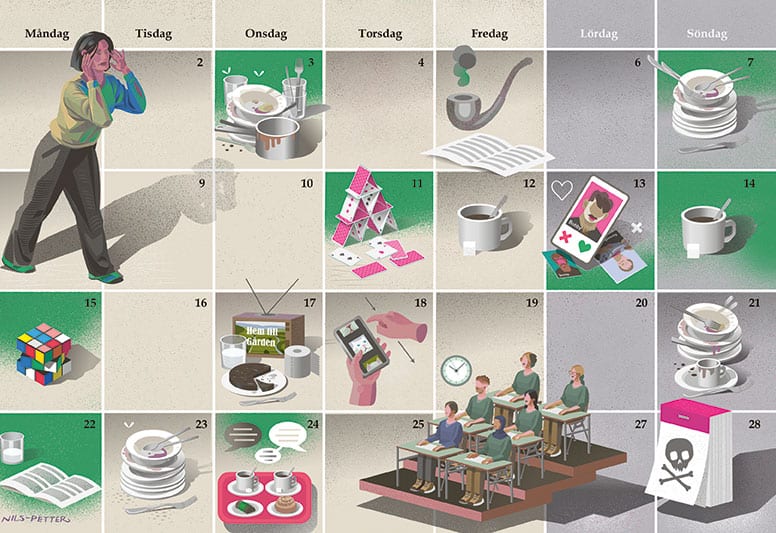

In a nutshell, procrastination is about loss of control; your control over your own time has been eroded. It is caused by a combination of external stimuli and internal psychological mechanisms. Having clear and consistent priorities is one way to regain control.

“I usually advise people to spend five minutes deciding what is the most important thing to do during the working day. That should be your first task. Similarly, you can set a weekly goal for your research. Your research time should be scheduled.”

Alexander Rozental

Professor of psychology at Luleå University of Technology

Alexander Rozental, a professor of psychology at Luleå University of Technology, distinguishes between structural procrastination, (which is not actually procrastination, but simply an effect of the work environment), and individual procrastination. The latter is an inability to complete tasks even though you have plenty of time for them.

“The more time we have to complete a task, the further away the value of finishing it. Instead, we do things that are more immediately satisfying, tasks that are smaller and give us faster results. Like answering emails or making phone calls.”

Rozental uses the behavioural economics concept hyperbolic discounting to describe the calculation that governs procrastination. Simply put, we value gains that are close in time more than those that are further away. He has several corrective techniques that he can recommend – turning off distractions on phones and computers is the simplest.

Switching off teaching, administration and supervision is more difficult. Not to mention research grant applications or constant interruptions of a more or less urgent nature – like questions from journalists, for example.

“When it is external factors that impact your ability to get things done, we can call it structural procrastination,” says Rozental. “This applies to tasks that have shorter deadlines and that also often trump research in terms of urgency.”

With limited research time and their research funding increasingly reliant on external grants, many researchers find themselves caught in a trap.

“Those who scrape by on short-term contracts do not have the time to acquire the qualifications they need to be offered permanent employment. This is a dilemma that can cause a lot of stress, especially among young researchers. A senior lecturer with a permanent position is in a better situation, but is held back in their career by having few hours available for research.”

As a result, the psychosocial work environment itself can be a cause of individual procrastination. “You become less creative and find it harder to solve problems. It is often said that it is procrastination that has a negative impact on wellbeing, not the other way round. But the stress of having too much teaching also makes it harder to deal with things that require a lot of thought.”

The fundamental solution to structural procrastination is funding, he says. Researchers need more scheduled research time; higher education institutions need to fund more research positions.

However, it is important to distinguish between structural procrastination and a person’s own inherent tendencies towards hyperbolic discounting. Rozental is careful to emphasise that the work environment is the employer’s responsibility, but individual solutions can still help to improve the situation within certain limits.

“I myself am a great believer in collaborative research. In working together. It is time we did away with the image of the scientist as a brilliant loner.”

Group work with regular reporting is procrastination’s worst enemy. It makes people schedule research time, and there is accountability within the group. You do what you are supposed to do, and you report back to the group on time. People who try this method are often surprised, he says.

“You can get much more done than you think when you work undisturbed for an hour. In my research groups, we work a lot with ‘shut up and write’. We work together for half a day, with different parts of the same study, and report at the end.”

Rozental shares his advice in his book Dansa på deadline (Dancing on the Deadline), which was published over ten years ago. It is used as study material for the courses run by Student Health Services (Studenthälsan) to help students address procrastination.

Study coach Rebecka Selberg Zolland and her colleague Anna Sigvardsson, a student counsellor, note that people who are new to university need particular help. They are faced with bigger tasks than they are used to, a completely new study environment and longer deadlines.

“They need to learn new responsibilities regarding their studies,” says Selberg Zolland. “Some teachers support them, for example by giving assignments more often rather than setting a big exam at the end. That is good for everyone, but especially for those who are struggling.”

Rebecka Selberg Zolland

Study coach

The psychological resistance to getting started with a task can range from mild discomfort to severe anxiety. Not to mention shame – many people think they are the only ones struggling to get going.

“There are plenty of things you can do,” says Sigvardsson. “Watch Netflix, do the dishes – things that will give you an instant reward instead of subjecting yourself to the discomfort associated with starting what you need to do. But once you start, the discomfort usually subsides.”

Anna Sigvardsson

Student counsellor

Their courses have been given high scores in evaluations. “We cannot promise that you will stop procrastinating, but following the advice usually results in less procrastination.”

The reason that the course works so well lies within its own nature. The advice begins with how to start. And then how to keep going. By then, you have already put procrastination behind you.

“It is such an exciting area to work in. People often say ‘I work best at the last minute’. And in many cases students manage, pass the test or course and move on. Then they do not realise that there are negative consequences, because they succeeded,” says Sigvardsson.

But by the time the deadline arrives, they have often gone through many days of stress, performance anxiety and discomfort. “And what would have happened if they had started earlier? Would the result have been better?”

Five ways to prevent procrastination

- Switch off anything that is not relevant to your work, (e.g. phone notifications and email pop ups on your computer).

- Do a check-in with yourself at the start of the day – what is your most important task today?

- Schedule when the task should be done – not just the deadline.

- Coordinate with other people, (e.g. by presenting the results of half a day of writing to a colleague).

- Work in focussed sessions (e.g. 30 minutes free from distractions, a 2-minute break, followed by another session).

Source: Alexander Rozental