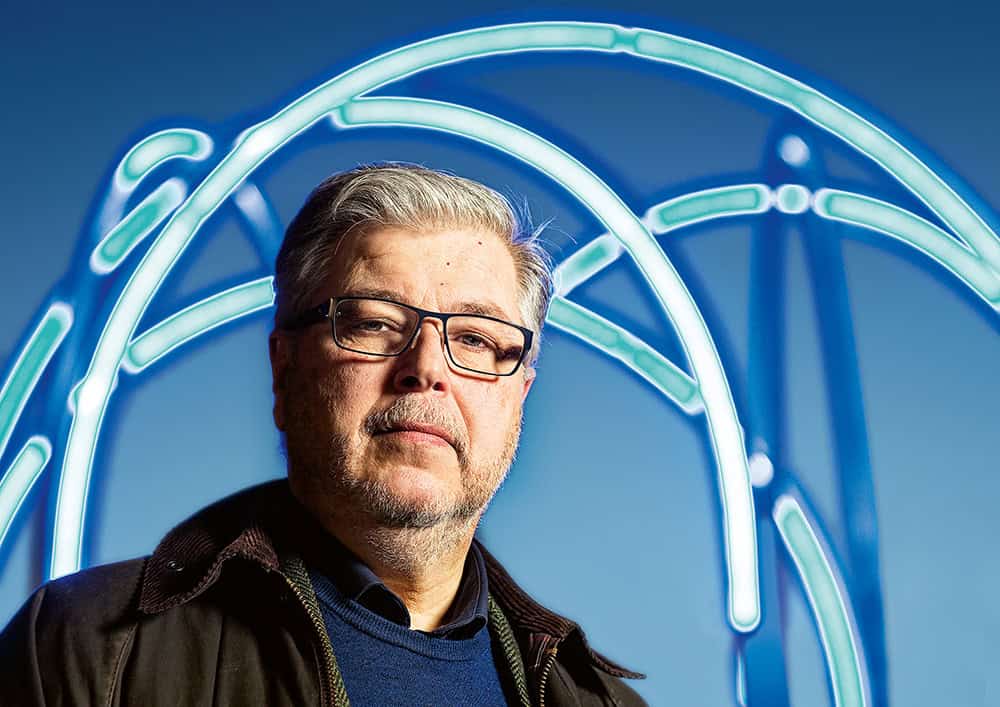

Torgny Larsson’s aluminium and argon artwork Energitemplet shines outside the window. Without its bright blue glow, it would be almost completely dark. When genocide researcher Tomislav Dulić came to Uppsala University to study Russian almost 30 years ago, he actually dreamed of becoming a journalist. Instead, he eventually chose to do a master’s programme in East European Studies. When he said he wanted to write a thesis on Russia, a professor urged him to use his language skills in some other way. So he decided to write about the July 1914 crisis from a Serbian perspective instead.

He went on to do a doctorate, where he continued in the same direction. His PhD project was on the subject of the fascist movement Ustaša in the Independent State of Croatia and the Chetniks, a Serbian nationalist movement, specifically about the violence of both organisations against people in rural areas during the Second World War.

“It really only came about by chance. That’s often the case in research, that you stumble into things by accident.”

Since then, he has become a professor at the Uppsala Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Until the beginning of this year, it was called the Hugo Valentin Centre, named after the Uppsala historian Hugo Valentin, who was one of the first people in Sweden to write and talk about the Holocaust and who wrote regular reports during the war about how Nazi Germany was murdering Jews.

The change of name has been criticised from several quarters. For example, Aron Verständig, Chair of the Official Council of Swedish Jewish Communities, wrote in an opinion piece in the newspaper Upsala nya tidning in January 2025 that Uppsala University had devalued Hugo Valentin’s fight against Nazism by the changing the name. In a letter sent to Anders Hagfeldt, Vice Chancellor of Uppsala University, 93 Swedish and international researchers demanded that the name change be rewoked.

Tomislav Dulić…

… is a 56-year-old professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Uppsala University.

He is a historian who speaks Russian, Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Swedish and English. He also uses French and German in his research.

Outside work, he enjoys playing chess, fishing or renovating his summer house.

Tomislav Dulić is of the opinion that the name change reflects a change in the centre’s activities. It was founded by merging the Centre for Multiethnic Research and the Uppsala Programme for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. The latter was set up in 1999, as part of the then government’s investment in research and dissemination of knowledge about the Holocaust. Dulić was the programme’s first doctoral candidate.

When a name was needed for the newly merged organisation, the decision was made to name it after Hugo Valentin. A couple of years ago, the funding for half of it was withdrawn, and only the Holocaust and Genocide Studies programme remained. As it is an approved subject in Uppsala, where Dulić is also a professor, they wanted to clarify what the centre is about.

“There is a master’s programme, and we are currently looking into starting an undergraduate programme. So it’s quite logical that we should also clearly link the name to the subject area. Unfortunately, the change of name gave rise to some strange insinuations that there were almost anti-Semitic motives underlying the decision. This is not the case of course, and the proposal had overwhelming support among staff.”

Dulić is currently working on a book about the 4,000 Yugoslav prisoners of war who were shipped to Norway as slave labour during the Second World War.

“The Second World War is what I have worked with most. I am a historian and prefer to work with archival material rather than the often scant sources you are forced to use if researching the present day. That’s nowhere near as exciting, and you often can’t get hold of classified material that might provide detailed descriptions of perpetrators’ decision-making processes, för example.”

”I am a historian and prefer to work with archival material rather than the often scant sources you are forced to use if researching the present day. That’s nowhere near as exciting.”

Around a hundred of the prisoners managed to escape to Sweden, Dulić says, with about forty of them coming to Uppsala. He explains that 64 per cent of the 4,000 Yugoslav prisoners were killed. He compares this with the 100,000 Soviet slave labourers in Norway during the same period, of which 15 per cent died. “So there is a huge discrepancy between the death rates. And then the question is: why? There are several possible explanations that I am trying to examine.”

His sources include the National Archives in Stockholm and the Norwegian National Archives, where he has analysed court proceedings in treason cases. He has also examined archive material from a war crimes commission in Yugoslavia and the archives of the Yugoslav Legation in Stockholm, which are in Belgrade.

Part of his research looks at the violence perpetrated by guards against prisoners. The latter can be divided into two categories during different periods of the war. The German SS ran the camp from 1942 to 1943, when the German Wehrmacht took over. There was also a group of young Norwegian men who worked as camp guards, mainly because they were poor and needed the money.

“This is a big issue that people remember in Norway. A lot of people were found guilty of treason after the war, and the interrogation records have been preserved. It makes for very exciting reading, because they were not as indoctrinated as the SS men. It will be particularly interesting to see who among them committed murder in the camp.”

Most of the prisoners were Yugoslav partisans, mainly men of military age. There were also smaller groups of nationalists that the Germans wanted to get rid of, as well as a slightly larger group of civilians of various ages and convicted criminals of various ages from what was then the Independent State of Croatia.

Dulić wants to find out how perpetrators reasoned and thought about committing murder. He uses as an example a story from his source material about a person who killed a prisoner. When asked why he did it, he replied that he ”wanted to see” what it was like to kill. Chance can make people behave badly. But choices can also be more deliberate, he says.

“There were certain advantages to be had from committing violence acts. In the reward system that existed at the time, people who actually participated in the violence were perceived positively by the German commanders and could also benefit from participating in the violence. Then there were others who tried in different ways to avoid taking part, including by fleeing to Sweden. A few even helped the prisoners by giving them food and cigarettes.”

Previous research has shown what happens when people are put in a context where the guards’ job is to get as much work out of prisoners as possible before they die. That is basically what happened with the Yugoslav prisoners of war, says Dulić.

He is also looking at the prisoners’ different strategies for survival. Some made themselves valuable to the Germans by co-operating, and some took on roles that involved participating in violence against other prisoners. Around ten collaborators were beaten to death by the prisoners themselves after liberation. Others tried to escape, including the hundred or so who made it to Sweden, he says.

He describes how one of those who fled to Sweden was Jewish, but he had managed to hide this from the Germans by assuming the identity of a dead person. A few years ago, Dulić was contacted by the man’s son, who is now a professor at the University of Tartu in Estonia. They have stayed in touch since.

People from the former Yugoslavia sometimes contact us to enquire about where their relatives’ remains are buried. In Sweden, some can be found in a cemetery on the island of Frösön and some in the cemetery in Jokkmokk, says Dulić.

Since the terrorist group Hamas carried out its terrorist attack in Israel on 7 October 2023 and the conflict in Gaza blew up, a fundamental question in the debate has been whether what has subsequently happened in Gaza should be regarded as genocide. Amnesty International, for example, has stated on the basis of its own investigation that it believes it to be genocide. Last spring, the United Nations Special Rapporteur also stated that Israel had violated the UN Genocide Convention in several ways. This was dismissed by both Israel and the United States.

Several researchers in Sweden also criticised the report, describing it as more a case of war crimes than genocide. At the time of writing, Israel and Hamas have agreed a ceasefire.

Tomislav Dulić has been invited to give various presentations and participate in discussions on the Gaza conflict. “Last spring I gave one where I gave, not so much my own view on whether it is genocide or not, but more what I thought, on the basis of previous court cases, would be the outcome when it is tried at the International Criminal Court.

The concept of genocide has not changed at all, he says. It is the interpretation of the concept that has shifted.

“In the vast majority of cases where it’s not genocide, it’s usually either a war crime or a crime against humanity, and there is no hierarchy between these offences. So it is no less serious to categorise mass killings as crimes against humanity rather than genocide.”

“In the vast majority of cases where it’s not genocide, it’s usually either a war crime or a crime against humanity, and there is no hierarchy between these offences. So it is no less serious to categorise mass killings as crimes against humanity rather than genocide.”

He describes how genocide has generally become an umbrella term.

“People have this idea that if you murder a lot of people because they belong to an ethnic group, then it’s genocide. But it’s not.”

For something to be categorised as genocide, the intent must be to eradicate the group completely or in part, he explains.

A court must therefore prove that specific intent in order to bring a verdict of genocide.

“There have been actions that were crimes against humanity that have killed many more people than events that have been defined as genocide. This includes crimes committed by communist regimes against ‘class enemies’. The Genocide Convention only protects ethnic, religious or racial groups.”

Is what has happened in Gaza genocide?

“Based on the reasoning of the ICJ, (International Court of Justice in The Hague, editor’s note), in similar cases, I am doubtful that there will be a guilty verdict. However, it will depend very much on the arguments and evidence presented when the crucial question of intent is discussed.”

Tomislav Dulić is in the process of completing a project on the culture of remembrance of the Second World War, funded by the Swedish Research Council.

After that, he plans to conduct a comparative study of resistance movements in the former Yugoslavia and France. After reading French literature on the subject, he became interested in the differences in the magnitude of violence. He has been granted funding by the Franco-Swedish Foundation to spend six months at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales in Paris this autumn.

Research into the Holocaust and genocide

After completing a master’s degree in East European Studies, Tomislav Dulić began his doctoral studies in 1999.

His doctoral thesis, completed in 2005, was called Utopias of Nation: Local Mass Killing in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1941-42.

He is currently writing a book about the 4,000 Yugoslav prisoners of war who were transported to Norway during the Second World War.

He is also completing a project on the culture of remembrance of the Second World War in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Croatia.