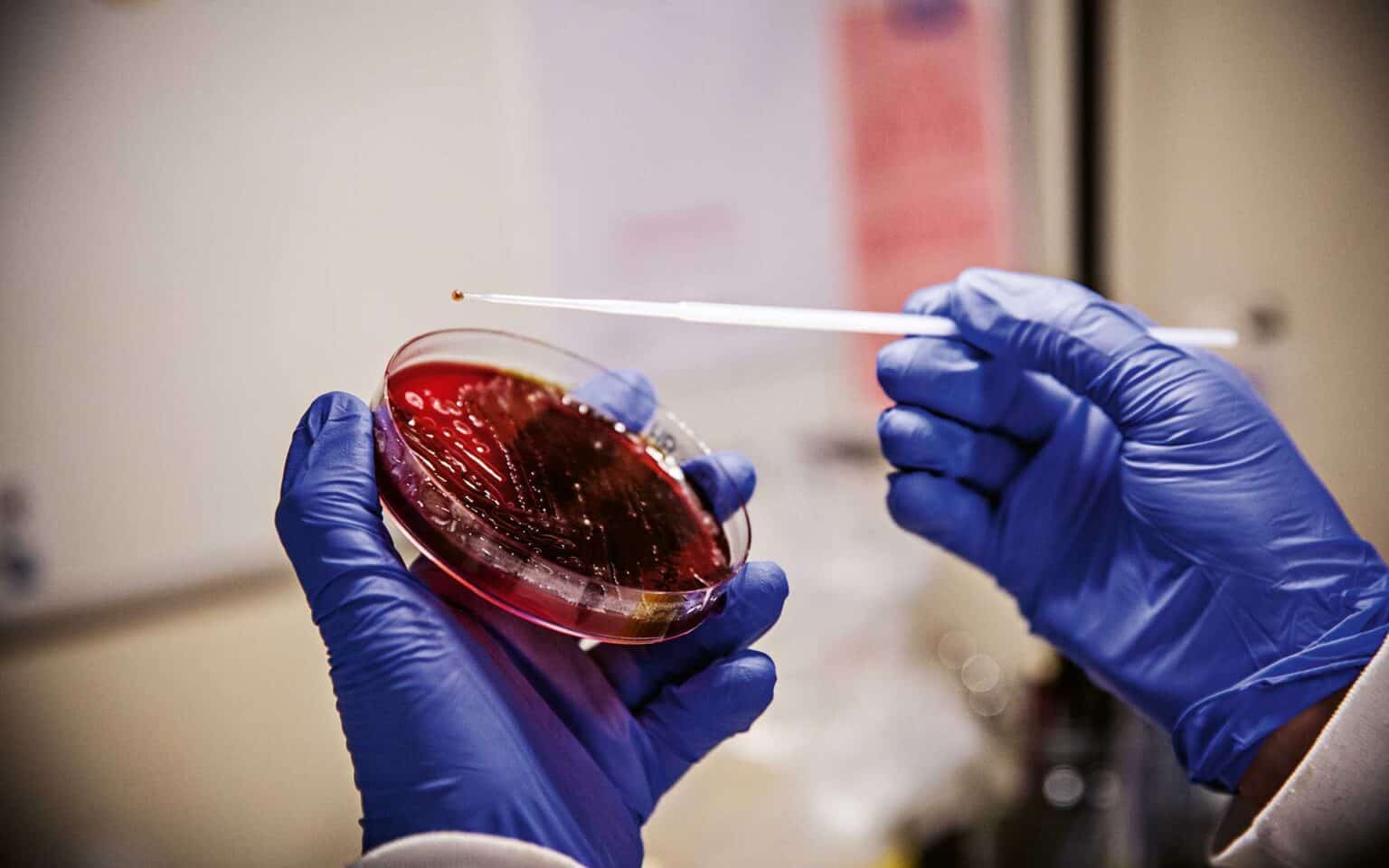

At the end of December 2014, doctors found a bacterium in a wound on a patient in Kungälv. After being cultured for 24 hours at 30 degrees, the bacterial colony, just over two millimetres in size, was circular, moist and soft. The bacterium turned out to be of a previously unknown variety and was freeze-dried, poured into a glass vial and placed in a box in a cold room in a basement in Guldheden in Gothenburg. It was labelled CCUG 66741. It would remain there for several years before some researchers decided to bring it back to life.

Bacteria were one of the first life forms to appear on Earth, and they have been extremely successful at spreading. Today, there are virtually no environments where bacteria cannot be found. Neither corrosive sulphur nor radioactive waste prevent bacteria from establishing colonies. A few billion years later, when humans began to spread across the world, the new species had no idea that the planet was already colonised by bacteria, which immediately also conquered the bodies of these bipedal animals. With the invention of the microscope, humans were able to see their colonisers for the first time, and shortly afterwards the search for and classification of new species began.

This has, by any measure, hardly been a success.

The number of species of bacteria in the world is not known, with estimates ranging from a few million to several trillion. Consequently, we do not know what proportion have been discovered by humans. But it is a matter of a few per cent, if that.

The archive where the bacterium from Kungälv lies in its freeze-dried sleep belongs to CCUG, Culture Collection University of Gothenburg, which is Sweden’s only public collection of bacterial strains, and the largest of its kind in Europe. Bacteria from all over the world are sent here to be identified and classified.

“We have almost 80,000 bacteria,” says Liselott Svensson, Associate Curator of CCUG.

It is almost 20 years since she joined CCUG in a substitute position. At the time, she had just completed her doctorate, with a thesis on how bacterial toxins affect human immune cells.

The bacteria collection began in 1968. The staff have not been here as long as the oldest bacteria, but long enough for people to wonder why they have stayed for such a long time. Because it is not just a couple of years in most cases, but almost 20 years at the same workplace.

“It’s a nice group that we have put together. The four BMAs, who have all been here for many years, are different but work well together,” says Svensson.

BMA is an abbreviation of biomedical analyst. An alternative abbreviation could be BD, bacterial detective. Given how small a proportion of the world’s bacteria have been characterised by humans, there is no shortage of mysteries to unravel.

“We constantly receive new bacteria and species, and new methods are frequently developed that enable us to learn new things,” says Svensson.

Elisabeth Inganäs, one of the detectives, describes her workplace using a metaphor from the agar plates where the bacteria are cultivated:

“It is a living organism that is constantly developing. That’s why people stay here.”

Inganäs usually familiarises herself with bacteria by smelling them. Some anaerobic bacteria can give off an odour that she describes as “a stable with a warm horse”. The odour can determine which tests they will conduct.

“But I still get fooled by bacteria that turn out to be something completely different to what I thought,” she says.

CCUG has two different laboratories, one for traditional biochemical analysis and one for gene sequencing, known as Sanger sequencing, where part of the genome is analysed. The bacteria can also be sent away to have the entire genome mapped through whole genome sequencing.

It was whole genome sequencing that was used on the unknown bacterium from Kungälv when Liselott Svensson and her colleagues decided to find out more about it. What they knew was that it had some resistance to antibiotics and that it belonged to the same family as E.coli and salmonella. “The reason it was picked up and whole genome sequenced was that it was from a clinical sample and it belonged to a group of bacteria where there are many known pathogens, and we wanted to investigate and describe this new species in order to be able to characterise any future discoveries of it.”

The new species, which was given the name Scandinavium goeteborgense, was presented in an article in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology in November 2019. The discovery even made its way into Gothenburg newspaper Göteborgs-Posten’s daily P.S. comic strip, drawn by Sture Hegerfors.

The Gothenburg bacterium was found to contain a new resistance gene to the antibiotic quinolone. Four years later, three more species in the same genus were described. However, these were not found in sick people but in soil and plants.

Given the proliferation of bacteria, it is not surprising that the bacteria sent to CCUG come from all sorts of places. About a quarter of them are in a public database, which is accessible through the CCUG website.

Ahead of our visit, Universitetsläraren’s reporter prints out a list of the past year’s additions. When Elisabeth Inganäs looks through the list, she points to two of the rows.

“Here are a couple of cute campylobacters,” she exclaims.

One was found in human urine, the other in pig faeces. Both were sent in by researchers at an American university. Because the study had not been published, the team in Gothenburg had to maintain silence about what they had received.

On another occasion, they received identical bacteria from two different researchers, but could not tell them that they were chasing the same ball, so to speak. Whoever got there first would get to publish their findings.

Anyone who has found a new species needs to deposit it with two different strain collections. The list we printed out includes Legionella bacteria from a Korean researcher who chose CCUG as one of the collections. The same requirement does not apply to all bacteria on which research is conducted, which creates a problem that Liselott Svensson and her colleagues discussed at today’s lunch break.

“Many researchers do research on bacteria that are not saved, so the studies cannot be repeated with the same bacteria.”

The list of last year’s new additions includes bacteria from a cow’s tongue in Denmark, from coughed-up slime from Japan, from Vietnamese soil and from Korean poplar bark. There are also samples from various types of industrial production.

“They probably have some kind of accreditation or certification and have to characterise any bacteria that they find,” says Svensson.

The latest bacterium on the list belongs to the species Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the bacterium that causes gonorrhoea, and was found in human blood.

“When they are unable to identify a bacterium to species or if it is an unusual discovery for the sample material, it is sent here,” says Svensson.

In addition to the freeze-dried bacteria resting in their glass vials, the archive consists of information stored in binders, which fill several long shelves. When new information about a bacterium comes to light, it is printed out and placed in the relevant binder. Summer is usually a good time to pick out one of the unknown bacteria to see if there is any new information. This summer, we were lucky enough to find a bacterium that had been found in lettuce and had lain freeze-dried for 17 years.

“When it came in, we could only see that it was a species we didn’t already have,” says Inganäs. “We did some new sequencing and it turned out that it matched a bacterium that had been published in 2023.” Its name, Winslowiella iniecta, was entered into the archive.

Almost half of the binders in the archive have a white label, indicating that their contents have been transferred to a digital archive. This work began four years ago.

Many of the bacteria are not allowed to rest for very long in their glass vials, but are put into labelled boxes and sent out into the world. In the corridor, there is a large map of the world, with white pins marking the places where someone ordered bacteria in one year, 2011. Most of the pins are concentrated in central Europe and the Nordic countries, but they are also scattered across other continents.

A vial of bacteria costs around SEK 800, and they are ordered mainly by clinical labs that use the strains to check different methods and by researchers who want to use them in studies. But orders also come from companies that develop analytical methods to determine species or obtain more information about the bacteria.

“We often have many strains of the same species, so there is a lot of variation,” says Svensson. “This is what makes us popular with companies who develop different methods.”

However, not just anyone can go to the website, look up a bacterium and then order a couple of glass vials.

“We only sell to other laboratories and to researchers, and we cannot sell to anyone that we are unable to check.”

The same answer was given to the Stockholm police a couple of years ago. The reason for their call was that several politicians had fallen ill after a Christmas party. The guilty bacterium had been identified as Shigella, and the police wanted to know if CCUG had sold it to anyone who might have a motive to poison a number of politicians.

Most of the bacteria in the collection are quite harmless. Many are considered good or friendly. But many bacteria would not be considered harmless if it were not for one of humanity’s most groundbreaking inventions, antibiotics. Much of the research conducted with the bacteria from the archive is part of the battle for resistance that has been waged between humans and invisible microorganisms since the invention of penicillin. Antibiotic resistance is sometimes called the silent pandemic. The number of deaths due to resistant bacteria is not known, with estimates ranging from 700,000 to over a million people per year. That figure is expected to rise sharply in the future.

Several methods can be used to analyse the genes of bacteria to learn about things like infectivity and resistance. But no matter how advanced the methods are, they can only tell us what the genes might express.

“Sometimes genes can be silent,” says Svensson.

Bacteria can thus contain resistance genes without being resistant. To find out what actually happens, researchers must go down to the protein level, known as proteomics. Researchers associated with CCUG are working to develop proteomics methods that are both faster and more accurate than the frequently time-consuming process of mapping genes.

That research is also important for the collection, as characterisation of the bacteria will be improved. The results are printed out and put into the binders.

“The more research that is conducted, the more we know about them,” says Liselott Svensson.

Most bacteria in Europe

CCUG in Gothenburg holds the largest collection of bacteria in Europe. A further 24 countries belonging to the European Culture Collections Organisations (ECC) have similar collections.

Some countries have more than one collection, and several collections also contain other micro-organisms.