Bo is nearing the end of his life. Between home care service visits, he thinks about why things have turned out the way they are. Why his son Hans is so lonely and why Bo finds it so hard to talk to him about it. And why is Bo the way he is?

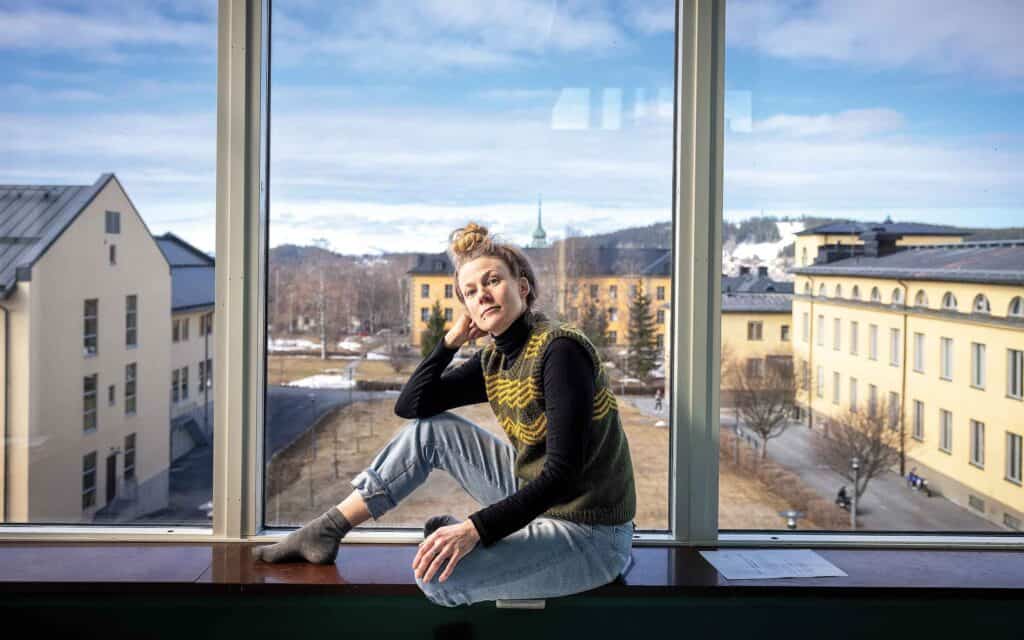

In her research and writing, Lisa Ridzén, a doctoral candidate in sociology at Mid Sweden University in Östersund, wants to battle stereotypes and ideas about men who live in sparsely populated areas. Or more precisely, in the countryside in northern Sweden, as she describes it.

Partly, this is to show the vulnerable and more unexpected sides of these men. In Ridzén’s debut novel, The Cranes Fly South, Bo thinks back to how he disliked his own father, ‘the Old Man’. At the same time, Bo can see traces of the Old Man in his own parenting, through how his son Hans is and how he deals with life.

In her work on her upcoming thesis, Ridzén is collecting life stories from men who live in rural Jämtland. She is talking to both Swedish and Sami men. The youngest is in his twenties and the oldest is over eighty. She plans to complete her thesis in 2026, but from what she has seen so far, a lot has happened over the generations she describes in her book, even if her own stories are fictional.

There have been changes in men’s relationships, vulnerability and empathy, says Ridzén. “Simply in how people talk about relationship building. There you can see how the strong patriarchal values of gritting your teeth, that a real man deals with things himself and that you cannot show any vulnerability are ideals that are less strong among the younger participants in the study.”

It is also the building of relationships that her debut book focuses on. Ridzén wants to show how Bo has been shaped by the place he lives in, and by his father’s tough manner. She writes about Bo’s mother, who constantly has to defend Bo against his father, and about how Bo wants to run away from home as soon as he can, which he also does.

She depicts the lifelong relationship between Bo and his friend Ture, who is a different kind of man, but at the same time not different. Ture wants to find himself, travels around the world and moves to the big city.

Bo misses his wife, who has moved to a dementia care home and no longer recognises him and Hans. Bo curses himself for being in some ways the same kind of father to Hans as the Old Man was to him, even though he has also been a different kind of father. At the same time, Hans is a different son than Bo himself was to the Old Man. Hans is present towards the end of Bo’s life, whereas Bo was not during Old Man’s. But why is Hans so lonely?

“I did not just want to look at different generations, but also at, for example, different social classes and sexuality. How we are shaped by different experiences and how they lay the groundwork for us to live good lives.”

Lisa Ridzén goes on to talk about the stereotypes and preconceptions that she wants to explore in her research. She does not want to reveal too much about her findings before her thesis is complete, but she takes the example of one of her younger interviewees. In many ways, he is quite stereotypical at first glance. He likes snuff, snow scooters and hunting.

“All that has not changed from generation to generation. But when I ask about relationship building and the importance of crying with your best friend, he wonders why he shouldn’t. ‘You feel worse if you don’t cry,’ he says”

Ridzén sees a younger generation where men are aware of masculinity norms, and of the destructiveness of those norms. There is an awareness of mental ill-health that is linked to how people talk with the people closest to them.

“This comes very much from the traditional ways of dealing with problems, such as gritting your teeth, putting on a brave face and all that. And it feels quite hopeful actually. Having said that, it is still the case that younger people feel that masculinity norms can be problematic.”

After studying at Umeå University and living for a while in Australia, Lisa Ridzén is now back in the village of Hegled outside Östersund, where she grew up. She lives in her grandfather’s old house, and her parents also live in the village. Lisa Ridzén grew up in a nuclear family, with teacher parents who still live together and with an older brother.

It was also here in the village that Ridzén got the idea for her book, when she was in her father’s workshop looking for screws in the spring of 2021. Saved in a box, she found her grandfather’s home care notes. Short comments about how the visits went, so that the next carer who visited would know. Some of the notes were written by her father.

“It was there and then that I realised that I wanted to write about an older man’s perspective.”

The Bo in the book is not Lisa’s real grandfather and Hans is not her father. None of the characters is a straight portrayal of a real person she knows, Lisa Ridzén clarifies. The home care staff’s notes have also been rewritten so that the people who wrote them will not be able to recognise themselves.

But even though Bo and Hans are fictional, their characters are inspired by ”almost all the men” that Lisa Ridzén grew up with, knows and has in her life. Characteristics and reflections from different people have been mixed together. She has also invented some.

That said, Lisa Ridzén was close to her grandfather as she was growing up. He was alone quite early on when her grandmother passed away. Towards the end of his life, Lisa Ridzén helped him a lot in his everyday life.

“In many ways, my grandfather and Bo are similar, but my grandfather was nowhere near as angry and grumpy as Bo can be sometimes. They share a kind of collective generational experience of being a rural male, a working-class man who thinks political ideals are important. My grandfather was active in the Social Democratic Party and he was a supporter of the union and all that.”

She does not want to tell her grandfather’s entire life story, but she describes how he was abandoned as a baby by an unknown mother in Stockholm. A foster home placement in Västerbotten in northern Sweden and growing up in a world of hard work meant that there was plenty for him to complain about.

“But he was always able to see things positively somehow. I always try to remember that.”

Her grandfather was a great role model.

“He had a fantastic ability to fit in and be content. My grandfather had an incredible thirst for life and curiosity about people, but at the same time he was very non-judgmental. A very pleasant man to be around.”

It is also here, in the place where Lisa Ridzén grew up, that she finds a group of people who face the prejudices and stereotypes she now wants to investigate. It is problematic that the men who are and have been around her are often portrayed in a stereotypical and prejudiced way, she says.

“Parts of that stereotype are true, of course. I usually get asked if this grumpy Jämtland man does not actually exist, but yes, he does and I know a lot of them. But the grumpy Jämtland man is not grumpy all the time. He is also sad sometimes and it may sound a little trite, but the grumpiness is not the only aspect of these people’s lives.”

Parallel to her discovery of the home care notes, Lisa Ridzén started an authors’ course in Stockholm. She was pregnant and began writing out the notes, which led to short stories about the main character Bo. When her daughter was born, Ridzén began trying to put the stories together into a novel when the baby was asleep.

It was completely different from the academic writing she does as a doctoral candidate, she realised.

“It felt very exploratory. I was feeling my way and didn’t know at all what the overall story would be. But with Bo’s story it was very clear. I had it all there.”

Writing fiction is something that she has really always both wanted to do and has done previously. When she was an undergraduate at Umeå University, and at the same time was working as a sex educator at the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education (RFSU) as a sex educator, her writing began to take off. She wrote erotic short stories, though without any ambition to publish.

When Ridzén was on sick leave with rheumatism for a while, she wrote even more. The short stories were edited into what actually became her first novel. “It was never published. But that’s when I understood that writing fiction was a lot of fun!”

Fiction and academic writing complement each other, and Lisa Ridzén is inspired by people who move outside the box. That is how she would also like to be.

“For me, getting a doctorate and doing a PhD programme is a lot about trying to find where I want to be academically. It is fun to work with language as a craft, and I have quite a hard time fitting into very scientific templates and publishing an article in academic English. Which is incomprehensible to most people. That kind of knowledge is also very important. I certainly do not mean that it should not exist. But that is not where my heart is.”

Ridzén wants to continue in academia, even though her writing has taken off. Her thesis defence is expected to take place in 2026. She refuses to answer which is the most fun, being a researcher or an author.

“Yes, I really want to continue in academia. It is great to be able to think and talk with others about society, and to be able to write about it. We will see what kind of positions there are, but I really have a dream job.”

A major motivator for Lisa Ridzén in her research is mental ill-health and a worrying suicide rate among men in rural areas. “In order to change that, it is important that we talk about masculinity, vulnerability and relationship building.”

She describes a feminist dimension to studying masculinity and men.

“For everyone who lives with men and loves men, whether it is a romantic relationship, a father or a brother, destructive masculinity norms have consequences. For everyone and for the whole of society.”

“For everyone who lives with men and loves men, whether it is a romantic relationship, a father or a brother, destructive masculinity norms have consequences. For everyone and for the whole of society.”

Right now, she is writing a new book, due to be published next year. It is a standalone sequel set in the neighbouring village. This time it is about younger men and the main characters are new.

Lisa Ridzén

…is 36 years old, a doctoral candidate in sociology at Mid Sweden University in Östersund and an author. Her debut novel, The Cranes Fly South, was published in January and is about Bo, a man who lives in a village in Jämtland and is nearing the end of his life. Between home care visits, Bo reflects on why he is the way he is, as a man and as a father to his son.

Lisa Ridzén grew up in the village of Hegled outside Östersund, where she lives with her daughter, partner and dog. In her spare time, she enjoys gardening, sewing and cross-country skiing.

About her research

Lisa Ridzén researches masculinity norms. In her thesis, due to be completed in 2026, she studies Swedish and Sami men in the Jämtland countryside and in southern Saepmie. Specifically, she examines their life stories to analyse how colonialism and masculinity norms impact their lives. Lisa Ridzén also teaches gender studies.