In the summer of 2013, Jan Björklund, who was Minister for Education at the time, floated the idea that universities and colleges should be run as foundations rather than state authorities. After initially demanding an extended consultation period on the grounds that the proposal was so difficult to formulate an opinion on, the higher education sector came to the unanimous conclusion that it was not a very good idea. The government dropped the proposal.

However, the Ministry of Education did not agree with the sector that the proposal regarding foundations was complicated. It emphasised that higher education institutions would have greater financial freedom if they were run as foundations.

It was necessary in order for them to be able to compete internationally and collaborate with other countries more easily.

These are also some examples of the arguments that the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions, SUHF, has advanced for shifting from the governance model that is in place today, where universities and colleges are state administrative authorities.

“If we are really going to be able to take academic responsibility for our activities – research, education and external collaboration – we also need to have frameworks that fully allow it. Frameworks that enable us to be competitive, both nationally and internationally. In that respect, we can see that there are some limitations with today’s organisational form,” says SUHF chair Hans Adolfsson.

Hans Adolfsson

Chair of SUHF

For SUHF, the question of organisational form is high on the agenda, and they have an expert group for analysis that is working with it, he explains.

“We see this as an aspect of academic freedom and institutional autonomy. By that we mean how can we ensure arm’s-length distance from the state and the government?”

Adolfsson brings up a number of limitations that the current organisational form has, including the scope to sign agreements. There are also restrictions when it comes to receiving donations, how investments can be made, how real estate can be owned, how funds can be transferred and how profits can be distributed from holding companies that higher education institutions run.

In his reasoning, Hans Adolfsson comes back to one issue:

“Academic freedom and the desire for greater autonomy. If academic freedom is to be guaranteed, the state cannot step in and dictate exactly what is to be taught or researched, because then you have stepped in and interfered with academic freedom.”

SUHF’s analysis group is working with a number of investigations related to academic freedom. One of these involves reviewing the current organisational form and proposing how it could be improved, something that is more relevant now than it has been for a long time, says Hans Adolfsson.

“To a very high degree. We see more and more restrictions on academic freedom, more and more desire to control activities at detailed level. And the government can do these things as long as we are state authorities.”

“To a very high degree. We see more and more restrictions on academic freedom, more and more desire to control activities at detailed level. And the government can do these things as long as we are state authorities.”

Hans Adolfsson

He sees Sweden as unique in an international context when it comes to the separation of higher education and research from the state. For example, Finland has a different structure, where universities and colleges are further removed from state governance.

Similar structures also already exist in Sweden, which could be a way forward when it comes to the organisational form of higher education institutions.

“In some other parts of the state apparatus, we have a greater distance from direct control. For example within Swedish Radio and in other types of public law organisations that are adapted according to their activities in order to be able to have limit direct control. And it is something similar that we (SUHF, editor’s note) are also looking into,” says Hans Adolfsson.

Going back to Jan Björklund, it wasn’t really he who started the process. When the right-of-centre alliance parties won the election in 2006, they promised to change higher education fundamentally, not least that higher education institutions would cease to be authorities.

The year after the election, Björklund’s predecessor, Lars Leijonborg, appointed a commission of inquiry which a year later produced the report ‘Independent Higher Education Institutions’.

The report proposed that Swedish higher education institutions should no longer be state authorities from January 2011.

”At the same time, they, (the higher education institutions – editor’s note), would remain in the public sphere. It is a question of deregulation, not privatisation,” said the head of the inquiry and professor of political science Daniel Tarschys in an interview in Universitetsläraren after the report was presented.

Via a bill on increased freedom for the universities, this then led to the 2011 autonomy reform. And it was somewhere around that time that Shirin Ahlbäck Öberg, a professor of political science at Uppsala University, became interested in state-sector higher education institutions.

She conducts research on the management of public sector organisations.

“When the autonomy reform was launched, it became very clear to me that state-sector higher education institutions are an excellent subject for analysis, and a subject that needs analysis,” she says.

Shirin Ahlbäck Öberg

Professor of political science at Uppsala University

In the spring of 2023, Ahlbäck Öberg presented her paper “On Academic Freedom”, as part of SULF’s publication series. There she argued that the state-sector higher education institutions’ organisational form is not stable because it means that universities and colleges have dual roles.

As an administrative authority, a higher education institution reports to the government, with its responsibility for implementing political decisions made and communicated in the constitution, in appropriation documents and in government assignments. At the same time, they must be institutions for free higher education and research.

Like Hans Adolfsson, Shirin Ahlbäck Öberg thinks that the issues of academic freedom and the institutions’ autonomy are more important than ever.

“From the Magna Carta onwards, there are lots of international agreements and laws that emphasise institutional autonomy. It is therefore essential for higher education institutions to maintain an arm’s-length distance from politics, the market and ideological organisations. It is a matter of legitimacy and authority.”

On the other hand, it is not self-evident that the Swedish form of governance cannot be reconciled with autonomy, says Ahlbäck Öberg, and uses the example of courts. Through legislation, courts are guaranteed independence and politicians cannot interfere in their work.

Academia, she says, does not have the same clear dividing line with regard to the state.

“It is deeply disturbing how politically controlled activities have become. And this has increased, from the so-called freedom reforms of 1993 onwards. You could put it this way: if this form of authority has ever worked, it has been based on an informal agreement between the state and the higher education institutions. An understanding of where the line is drawn and of how to maintain it. But I would say that agreement is broken now.”

”If this form of authority has ever worked, it has been based on an informal agreement between the state and the higher education institutions. An understanding of where the line is drawn and of how to maintain it. But I would say that agreement is broken now.”

Shirin Ahlbäck Öberg

She offers as an example the way the current government chose to shorten the mandate periods of the boards of higher education institutions last year.

“But also the way the previous government chose to organise the ethical review process shows, in my opinion, that they regard state-sector universities the way they regard all other authorities. That you can regulate matters by law and place supervision under another state authority.”

At the time of our interview, Ahlbäck Öberg had just handed in a report on what she calls an authoritisation process, which she wrote together with Johan Boberg, a senior lecturer at the Centre for Higher Education and Research as a Subject of Study at Uppsala University.

In their report, they say that the state-sector universities are tightly controlled, which is contrary to laws and agreements that Sweden has entered into within Europe.

Even if politicians emphasise that they want freedom for higher education institutions, research funding, for example, has become more and more targeted, she believes.

“Overall, it actually gives a very worrying picture of the current situation. I have to say that when it was decided politically that a suitable form of organisation for higher education institutions is as an administrative authority, I wonder what their thought process was,” says Ahlbäck Öberg.

Lars Geschwind

Executive Director of SULF and professor at the Royal Institute of Technology

Lars Geschwind, a professor at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) and Executive Director of SULF, has researched the governance and organisation of higher education institutions.

“Universities and colleges are interesting in many ways, not least when it comes to governance and organisational issues. It is difficult to put them into a template that matches today’s organisational forms. A higher education institution is not a company, but it operates in a market. Nor is it an authority in the same way as the Swedish Public Employment Service or the Swedish Social Insurance Agency,” he says.

Higher education institutions are public sector organisations and part of the state, but with a special form of governance, Lars Geschwind continues. He describes the situation as a parallel power structure. A combination of state, market and academic oligarchy.

For SULF, the issue of the form of organisation is important, even if it is a somewhat lower priority than the issue of academic freedom for education and research, he says.

“In recent years, there has been a desire for political interference, regardless of party, which is something that we at SULF have talked about a lot. There is micromanagement in many ways, both in research and in education. It is very clear and tangible when you are both a higher education institution and a state administrative authority.”

But even if SULF is still interested in the issue, it is not entirely uncomplicated, says Geschwind.

“The consequences a change would have for our members need to be assessed in different ways. Although change would not necessarily be worse, we also want to test what could be done within the existing system.”

“The consequences a change would have for our members need to be assessed in different ways. Although change would not necessarily be worse, we also want to test what could be done within the existing system.”

Lars Geschwind

The fact that more frequent discussion about the organisational form has flared up is a sign that something has happened in the system, he believes. SULF’s opinion therefore is that it may be worth testing an alternative organisational form. “To actually assess what that would mean. SULF has not taken any other view on the matter,” says Geschwind.

A higher education institution’s organisational form has been changed in the past. For example when the higher education institution in Jönköping was privatised 30 years ago and the government turned it into a foundation university.

Today, it is called Jönköping University, and consists of a health college, an international business school, a technical college and more.

Agneta Marell

Vice-chancellor at Jönköping University

Vice-chancellor Agneta Marell started working at Jönköping University in 2017. She thinks that being a foundation has been good for Jönköping.

“It is a fantastically good form and it is very valuable that there is an alternative form that allows slightly different possibilities, but there are also challenges. So I think it is important to preserve foundations as an organisational form,” she says.

The benefits are seen within ownership and finances. As a foundation university, we have different ownership rights than the state-sector universities. Jönköping University owns its own real estate, says Marell.

“We can also manage our financial assets in another way than the state-sector higher education institutes. We can manage the foundation capital we have more freely than a state authority can, though it is not enormous.”

”We can manage the foundation capital we have more freely than a state authority can, though it is not enormous.”

Agneta Marell

When it comes to recruiting staff and admitting students, a foundation-run university also has greater freedom, says Marell. It is possible, for example, to decide oneself about certain admission criteria and to decide on compulsory union membership. When it comes to appointments, a foundation university can make more direct recruitments and appointments cannot be appealed.

“It is therefore important to use that freedom in a responsible way, so we do not bypass the national and international merit structure.”

When recruiting from other countries, a foundation-run university can also work faster when it comes to recruiting individuals or networking with research groups, says Marell.

Although she sees clear advantages for Jönköping University in being run as a foundation university, she wants to make it clear that she is not advocating for any particular type of organisational form for the sector as a whole.

“Every organisational form has its own advantages and disadvantages, and that does not have to mean that one solution is better than another. But I think that we should continue as a foundation and take advantage of the opportunities that it gives us,” says Marell.

When Universitetsläraren asks researcher Shirin Ahlbäck Öberg about which alternative forms of organisation would be suitable for state-sector higher education institutions, she starts by explaining that there are both differences and similarities between foundation-run universities and those in the state sector.

In the foundation universities’ agreements with the state and the state-sector universities’ appropriation documents, for example, you can hardly see any differences in the wording, she says.

“The directives are the same. So our assessment is that they (foundation-run institutions – editor’s note) are not at all as free as the politicians intended.”

Proper consequence and risk analyses are needed before it is possible to answer the question of which organisational form would be the best alternative, she says.

“You can’t just say that we will do what we did with Chalmers and Jönköping. It needs a much more comprehensive in-depth analysis and discussion than just an ideological point of view.”

“You can’t just say that we will do what we did with Chalmers and Jönköping. It needs a much more comprehensive in-depth analysis and discussion than just an ideological point of view.”

SHIRIN AHLBÄCK ÖBERG

But she is adamant that something needs to change.

“It is the existing organisational form as state administrative authorities that I am critical of. Some people then immediately think that I am an advocate of the foundation model, but that is not the case. My thinking is that the matter needs to be analysed carefully, and if you ask me, I think a public sector form would probably be a good idea.”

She supports the reasoning in the autonomy inquiry led by Daniel Tarschys, where he advocated for more independent universities.

“After all, that was a public sector law solution, which means that higher education institutions would be subject to the principles of openness and to certain aspects of labour law. Universities and colleges are responsible for and manage state funds and so on. I kind of don’t mind that. However, we are now completely vulnerable to political control when it comes to the content of academic activities, and that is problematic.”

The chair of SUHF, Hans Adolfsson, describes the higher education institutions’ organisational form as a construction based on trust.

“As long as the state thinks we are doing a good job and does not want to step in and control higher education institutions in detail, the arrangement we have works. But the day the state suddenly wants to step in and govern much, much more, then yes, we will definitely lose academic freedom.”

At SUHF, they expect to have formulated a position to be able to try to have a discussion about the question of the organisational form of higher education institutions sometime in 2024.

Hans Adolfsson feels that there is a degree of consensus among SUHF’s members that something needs to change.

“Of course there is always someone who has a differing opinion, but that is also precisely why we want to agree on a position that highlights the pros and cons. Where we can look at the different options available. A factual basis to use as a starting point,” says Adolfsson.

Lars Geschwind, Executive Director of SULF, also emphasises that thorough risk analyses are essential before any change to the organisational form of higher education institutions can be discussed.

Abandoning state authority status completely raises the question of job security, for example.

“Among our members, it is often highlighted that being a state sector employee is seen as something attractive. There is a lot to be said for wanting to continue to be employed by the state and to enjoy the conditions and benefits that being a state employee entails.”

He says that there a lot of positives in the current organisational form of higher education institutions.

“After all, we have four or five universities that are among the top 150 or 200 in the world,” says Lars Geschwind.

“Among our members, it is often highlighted that being a state sector employee is seen as something attractive. There is a lot to be said for wanting to continue to be employed by the state and to enjoy the conditions and benefits that being a state employee entails.”

LARS GESCHWIND

A possibly radical change in the current organisational form is probably a long way off, he believes. At the same time, things could happen faster than expected if the political will is really there.

“Should it be the case that politicians lift the lid for real when it comes to organisational reform, that higher education institutions should fall under public sector law or private sector law over the entire system when it comes to organisational form, or even become foundations, so that everyone has to compete with everyone, then there will of course be enormous consequences and I think that idea is dizzying for many,” says Geschwind.

Just as the right-of-centre alliance did eighteen years ago, the current Minister of Education, Mats Persson, also promised ”major reforms” for the higher education sector when he took office in 2022, including in an interview with Universitetsläraren. Whether that includes a change of organisational form is still unclear. The minister declined to be interviewed for this article.

He responds in an email that the government is working in different ways to “strengthen academic freedom”.

“Then the higher education sector must consist of a lively debate, and as Minister of Education, I encourage this type of questions to be discussed,” writes Mats Persson.

Footnote: Agneta Marell will leave her post as vice-chancellor of Jönköping University on 1 April.

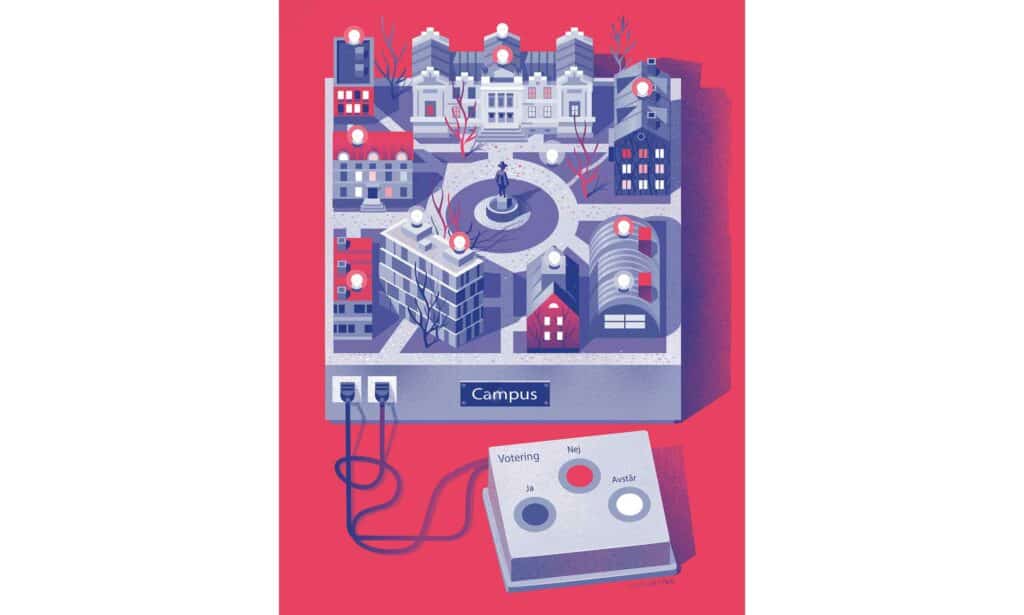

How the universities have been organized

1945 The universities of Uppsala and Lund as well as a number of specialist universities were run under state auspices. Stockholm and Gothenburg universities did not yet have the state as principal.

1963 The university and college committee at the time proposed that branches linked to the universities in Uppsala, Lund, Gothenburg and Stockholm be established in other locations. These branches established themselves gradually.

1977 A new higher education structure meant that new universities opened in several cities.

1993 The Higher Education Reform. The programme system and academic professional degrees were abolished in favour of subject education and bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees. The Higher Education Act and the Higher Education Ordinance became less detailed in their content.

1994 The government turned the University of Jönköping and Chalmers University of Technology into foundation-run universities.

2006 The right-of-centre alliance coalition won the general election and the Reinfeldt government announced radical changes for universities and colleges. Among other things, it proposed that they should no longer be state agencies.

2007 Lars Leijonborg, Minister for Higher Education and Research, appointed an inquiry to fulfil the election pledge of changing the organisational form of higher education institutions.

2008 Daniel Tarschys, now a professor emeritus in political science, presented a report entitled Independent Higher Education Institutes. He told Universitetsläraren that the report was about ”deregulation, but not about privatisation”. Its starting point was that universities and colleges should cease to be state authorities, which should minimise direct political control. Most referral bodies responded negatively.

2011 The Autonomy Reform was introduced as a result of the government bill A higher education sector for today’s needs – greater autonomy for higher education institutes.

2013 Minister of Education Jan Björklund floated the proposal that all colleges and universities should be foundation-run. The proposal was abandoned quickly after unanimous criticism from the higher education sector.

2022 Minister of Education Mats Persson took office. In an interview with Universitetläraren, he promised ”major reforms”.

2023 Mats Persson decided to change the periods of office of the boards of higher education institutions. The decision drew criticism from several quarters within the sector. It was seen as an attack on academic freedom.

2024 SUHF intends to present the results of its investigation into an alternative form of organisation for universities and colleges.

Sources: The Swedish Government, the Swedish Research Council, Jönköping University, The Swedish Council for Higher Education The Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions (SUHF)