According to the Work Environment Act, your employer is responsible for your work environment, even if you work at home. And there is no legal right to work from home.

As Maria Baltzer, a case officer specialising in systematic work environment issues at the Swedish Work Environment Authority, explains in an email to Universitetsläraren, ”It is the employer who is responsible for ensuring that the employee has a good work environment, regardless of where the work is carried out. If it is not possible to ensure a good work environment, for example, in the employee’s home, the work must not be performed there.”

With the exception of certain regulations on workplace design, the same rules apply to the work environment in an employee’s home as in the workplace. But this is not unproblematic.

The issue has many different components

As SULF’s chief legal officer Carolina Öhrn says with some understatement, “the issue of working from home has many different aspects and components.”

“I can imagine that many university teachers experience the same situation, that there is no agreement whatsoever about working from home: no one asks them where they do their work as long as they take care of their teaching and other duties.”

Carolina Öhrn

“For university teachers and researchers,” she continues, “there is probably a lot that is unspoken about how and where they should work. I can imagine that many university teachers experience the same situation, that there is no agreement whatsoever about working from home: no one asks them where they do their work as long as they take care of their teaching and other duties.”

Carolina Öhrn

Chief legal officer, SULF

It is also rare that the issue of home workspaces and their design and layout becomes the subject of trade union disputes. “We only step in if things aren’t working for some reason – if there is some discussion about how to interpret something in the employment contract or the meaning of an individual agreement.

Then we have to deal with it primarily on the basis of the local working time agreement,” says Öhrn.

Hybrid working has become the new normal

The existing legislation was not designed for this new situation in working life, where hybrid working has become the new normal for professional groups that do not need to be at the workplace in person.

In a scientific article, Arbetsgivarens och arbetstagarens arbetsmiljöansvar vid hem- och distansarbete, (The legal responsibility of the employer and employee for the work environment when working from home and remote working), Johan Holm of Umeå University highlights the problems with the legislation.

He believes that when the workplace in many cases moves to the home, the organisation of work and the work environment become increasingly individualised and private, while the legal regulation of the work environment is based on a labour market where work is carried out primarily in a shared workplace. He brings up, for example, the risk of infringement of personal integrity if the employer is to exercise supervision over the employee’s workspace at home.

For university teachers and researchers in particular, the situation is contradictory, as chief legal officer Carolina Öhrn points out. On the one hand, the Swedish Agency for Government Employers states that it is the employer who decides whether you can work from home, even if you have non-regulated working hours.

Common in practice

On the other hand, it is common in practice that university teachers and researchers work from home, and this is also often mentioned specifically in some local working time agreements.

A common way to express it in local agreements is something like ‘Teachers must be available to work at the workplace to the extent that the activities of the institution and the work tasks require it.’

“Yes, it’s a bit woolly,” says ergonomist Stefan Oliv, who has a doctorate in occupational and environmental medicine and is affiliated with the Sahlgrenska Academy at Gothenburg University.

Stefan Oliv

Doctorate in occupational and environmental medicine

The fact that the rules allowing the possibility to work from home are a little vague also means in practice that the division of responsibility for the work environment in the home is a little unclear.

In practice, much is up to the individual employee. Oliv therefore believes that a dialogue between the employer and the employee is essential. “Dialogue is the very first step. It is important to talk about the work situation, especially if working at home begins to happen more regularly.”

Voluntary agreement

Stefan Oliv brings up some examples. If the work carried out remotely is of a limited scope, you cannot demand certain equipment for the home workspace, because an agreement on remote working is voluntary, he explains.

You cannot demand that the employer send equipment to your home if you work, for example, one day a week from home. In that case, the equipment in the home becomes the employee’s own responsibility.

“The employer must ask: What does it look like at home?”

Stefan Oliv

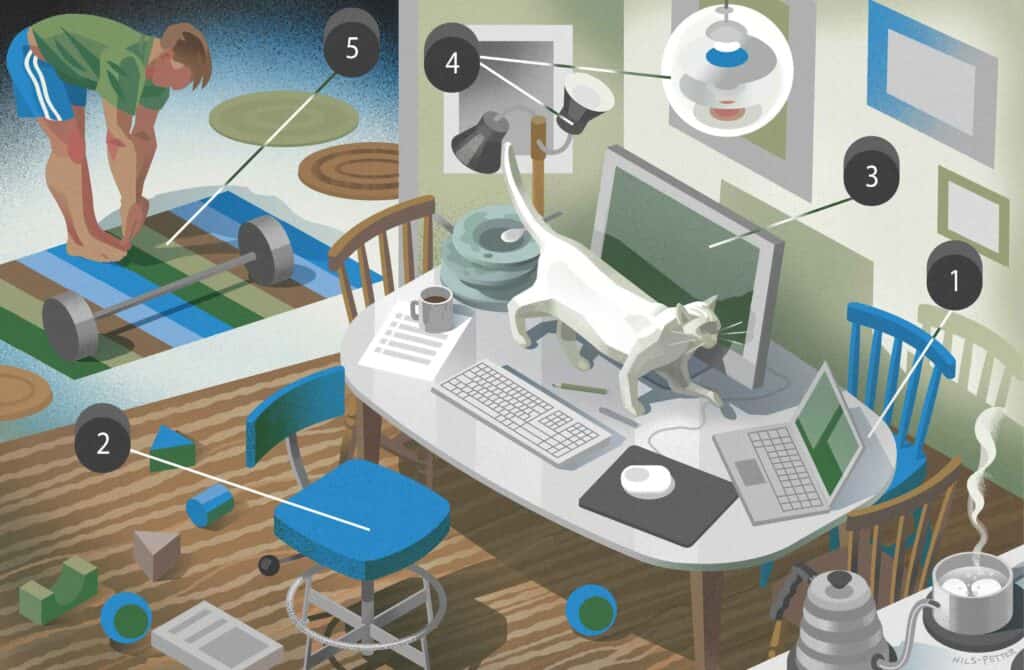

But Oliv also points out that the employer must make sure that the home workspace is functional. “The employer must ask: What does it look like at home? Do you have a proper place to work? A suitable place in the home where you can sit and work without being disturbed? And do you have a good chair to sit on? If I as the employee say that it is good enough for me for one day a week, then we have agreed on it.”

You can get away with poor ergonomics for shorter work periods. “If you work at home one day a week, or sometimes two, it can be okay to sit on a simple chair at the dining table in the kitchen. But if it becomes more than that, maybe two or three days every week, the working time at home starts to become so long that you actually need to take a proper look at what equipment you have. But as I said, it is actually the employer who must initiate such a discussion if someone wants to work from home.”

Different for longer periods

It is different if working at home becomes more frequent and for longer periods, for example if the employer has ordered you to work from home or if you have an agreement where the employer says that your main workplace is at home and that you only go to the office occasionally for meetings. “Then I would say that it is the employer’s obligation to ensure that you have the equipment required and an acceptable work environment at your home.”

“The alternative is for the employer to say no to remote working, but that is extremely rare in practice.”

Stefan Oliv

A third situation is if an employee requires some sort of adaptation of the workplace. “A person may have back problems that mean that they can’t sit all day, so in order to be able to do their job, they have to be able to stand and work. Then you can have a discussion about how the employer can contribute to adapting the home workspace,” says Stefan Oliv. “The alternative is for the employer to say no to remote working, but that is extremely rare in practice.”