In the 142 pages of his book Olyckliga i paradiset, (“Unhappy in Paradise”), the author Christian Rück mentions the concept of mental illness 42 times. Then he ends with an account of how problematic that term actually is.

The term mental illness covers so much, says Christian Rück. From the most severe states that require care to milder symptoms that do not need help. There is a danger that all suffering is put into one and the same medical model, he continues.

“That’s what I think the problem is, that when you talk about mental illness, it’s really all suffering in general. And when all suffering is called illness, you bring a lot of painful but non-medical suffering into the realm of illness. The suffering becomes abnormal and unacceptable.”

Prefers suffering

Because it is precisely suffering that he prefers to talk about.

“I know that this term (mental illness, editor’s note) is very popular and that many people appreciate its use. My fight against its use has been fairly unsuccessful in that way.”

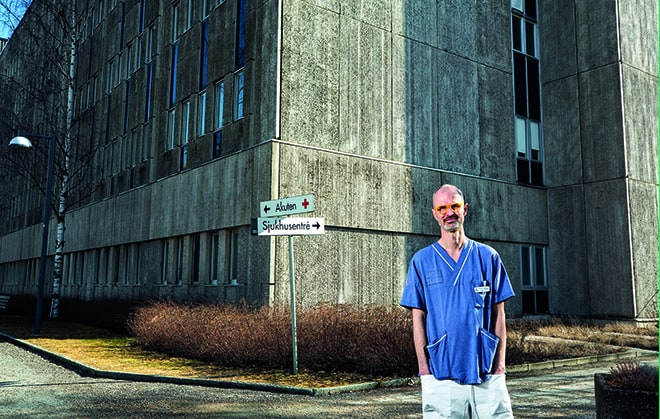

Christian Rück is a professor of psychiatry at the Karolinska Institute and senior physician at Psychiatry Sydväst at Karolinska University Hospital in Huddinge. He became interested in psychiatry because he was interested in people. The more biochemical part of the medical profession was not as exciting, as he puts it.

“I had some kind of slightly narcissistic idea that it would make a bigger difference if you met people in psychiatry, compared with if you removed someone’s appendix. For the latter, it may not much difference whether Doctor A or Doctor B does it. But I don’t know if that’s actually the case.”

In his book, he discusses how it is possible that more than a million people in Sweden use antidepressant medication. And why psychiatric diagnoses are skyrocketing when life in Sweden is as good as it is.

Since his book came out in 2020, however, Swedes have experienced a couple of years of pandemic restrictions and, at the time of writing, an economic crisis hangs over the country. Interest rates are increasing and electricity prices are soaring. So can we still call Sweden a “paradise”?

Christian Rück thinks so, and he does not believe that his book is out of date. The scope for living a good life is still better than it has been historically, and the situation in Sweden is also better than in most other countries.

Collective crisis improves social cohesion

A collective crisis like the pandemic, which affects everyone without exception, provides a huge boost for social cohesion. It builds a shared sense of community, he says.

“Interestingly, we saw a sharp decline in suicides during the pandemic years. Contrary to what we might intuitively think – that when everything gets weird and crappy in society rates will get worse. Certain types of crisis seem to be able to displace lesser problems. Something else takes over.”

The fact that the term mental illness covers a range of states that are perfectly reasonable in difficult situations also makes it unreasonable to strive to eradicate mental illness, he believes. “Creating expectations that you should feel 100% and that it is somehow wrong if you don’t feel 100%, I think that makes people feel worse.”

Rück points out that although there is no evidence that the pandemic has caused an avalanche of psychiatric problems in Sweden, certain individuals have of course been hit hard. “People have lost relatives, been diagnosed with post-covid or have worked themselves half to death in healthcare. But if we look at society as a whole, it doesn’t seem to have obviously had such disastrous consequences as we might think.”

The current tough economic situation will obviously affect many people negatively. At the same time, Sweden, with its experiences of the pandemic, has also prove9d to be strong society, says Rück. “The health care sector still has a lot of resources and the state has been able to compensate companies that were severely impacted during the pandemic. Historically, people have been hit much harder when there have been similar disasters in the past.”

More explained with diagnoses

Judging by the various public health surveys that have been carried out, Swedes feel neither better nor worse now compared to before, Rück points out. The Public Health Agency’s figures show that there has not been any dramatic increase in ill health among the adult population.

“We have, and have had for a long time, very many different psychiatric problems in the population. The level of suffering is roughly on a par with previously. The difference is that an increasingly large proportion of this suffering is now labelled with a diagnosis.”

However, there is an increase among younger people, especially women. “So there is reason for concern, in the sense that younger people seem to have more problems than older people. One wonders whether these problems will persist or whether they will go away as these people get a little older.”

Psychiatric diagnoses, however, make up just under half of sick leave in Sweden. Fatigue syndrome is the most common cause. But Christian Rück is actually almost as critical of the term fatigue syndrome as he is of mental illness.

“What I am critical of is that we have created a diagnosis with specific criteria which only exists in Sweden. There are similar problems in other countries which are given other diagnoses.

Little knowledge about fatigue syndrome

In addition, there is little knowledge about fatigue syndrome. “We don’t really know how to treat these people, and there are a lot of them now with long-term problems. We would have had to do this in a much more empirical way to know what the criteria for diagnosis should be.”

Between two armchairs in Christian Rück’s office stands a pile of empty cardboard boxes. Sitting in one of these armchairs, with the Universitetsläraren’s reporter on the therapy couch opposite, he talks about his current research on the subject of internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy, CBT.

He wants to reach out to those who live in places with less access to CBT. “The public healthcare service has not been able to offer CBT to all the people who would benefit from it. CBT treatment is helpful for the vast majority of psychiatric problems.”

Assisted self-help treatment

Internet-based CBT has developed in Sweden over the past 15 years, and Christian Rück’s studies began long before the pandemic broke out. But with a period of pandemic isolation behind us, it could hardly be more timely.

“It’s not so much about video meetings as it actually sounds, but more about assisted self-help treatment. You read, do some exercises and have contact with a psychologist for twelve weeks.”

Reaching out is something that Rück comes back to several times. In his role as an expert on psychiatry as part of a panel for the daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter, he answers questions from readers. “My aim is to influence the whole of society. I can’t really do that by producing research. My work for the newspaper is good because a lot of people read it. I would guess that a single answer there has been read more than the hundred-plus scientific articles I have co-authored.”

Another part of this strategy is social media. His Instagram account is full of insights from work, as well as from his favourite football team IFK Norrköping’s matches.

“It’s interesting to communicate with and try to arouse interest among people who are not obliged to listen to you. As a university teacher, you have a kind of privilege, in that people are booked into a schedule to come to a room to listen to you. You don’t have to sell yourself.”

Zero vision can cause fear

Over the years, Christian Rück has debated the problematic nature of a zero vision for suicide. A zero vision can contribute to stigma and guilt among relatives and healthcare professionals, he says. The danger, he believes, is that it creates a fear of the subject of suicide that makes it more difficult to help those who are close to it.

“If the question is whether there is an unnecessarily high number of suicides in Sweden, the answer is obviously yes. They are unnecessary because most people, if they continued to live, would change their minds. This is what you hear from people who have made serious attempts to commit suicide.”

If you have psychological problems:

If you feel unwell psychologically or if you have serious suicidal thoughts or plans, do not hesitate to seek help by contacting a psychiatric emergency department or calling 112. You can also contact:

Mind Suicide Line, through a chat function on mind.se or by telephone on 90101.

The organisation Jourhavande medmänniska (Neighbour on Call). Telephone 08-702 16 80.

Jourhavande präst (Priest on Call) can be reached by calling 112.

SPES – The National Association for Suicide Prevention and Survivor Support, telephone 020-18 18 00.

Children under the age of 18 can contact Bris – Children’s Rights in Society. Telephone 116 111 or via live chat.

If you need help with where to seek care, telephone 1177. They have a list of chat hotlines, advice lines and discussion groups for relatives.