“Guuudrun! Gudrun, come here! Good girl!”

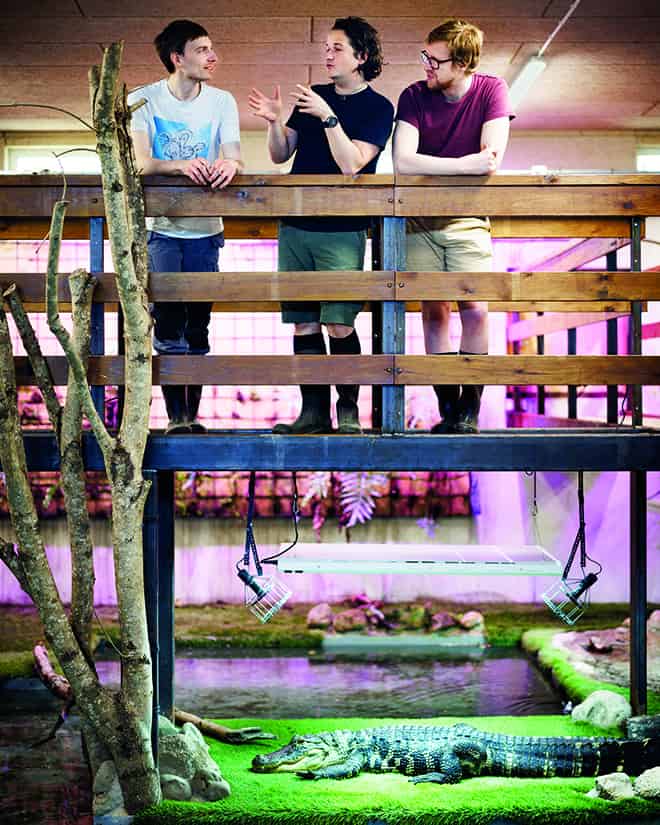

Scientist Stephan Reber calls out, and lightly taps the floor with the wooden stick he is holding. A large female alligator looks up out of the water in front of him, cautiously at first, but soon Gudrun climbs onto the artificial grass and takes a few waddling steps forward. Using long tongs, Reber fishes a dead mouse out of a plastic box.

The alligator tilts its head, opens its huge jaws and swallows the mouse, then turns back and slides back into the pool.

One of six alligators

Gudrun is one of six Mississippi alligators that came to Ystad Zoo in July 2021, where they are not only viewed by the park’s visitors, but also monitored by a research group from Lund University, which is studying their behaviour. They observe and film the animals, including when they eat, and follow their gazes to learn more about cognition, i.e. how the brain perceives, takes in and processes information. The purpose of the research is to study cognitive evolution, from the time of the dinosaurs, by studying some of the birds and reptiles that live today.

“We know that birds are dinosaurs and that crocodiles are birds’ closest relatives,” says research group leader Mathias Osvath. “The brains of today’s crocodilians are also very similar to the brains of the first dinosaurs, even though the lineages split 250 million years ago. If we can compare the abilities of crocodilians and some birds, we will get a pretty good picture of the major developments over the past 150 million years.”

Osvath is a docent in cognitive zoology and leads a research group within the Department of Cognitive Science. The group of 13 researchers studies animal cognition, an area that is relatively new within cognitive science in Sweden, he says.

“In my field, we are critical of the fact that there is so much focus on human cognition. Just looking at human beings is like reading a single sentence in a book and thinking you understand what the whole book is about.”

Were meant to be euthanised

In 2017, Osvath found out that six alligators were going to be euthanised in Great Britain. Lund University bought the animals, and at the same time hired the Swiss researcher Stephan Reber, who was then a recent graduate of the University of Vienna, where he had mainly studied communication in ravens, but also in alligators during a side project in the USA.

“I was more or less headhunted by Mathias Osvath, because he needed someone who could work with crocodilians. It paid less than an offer I had from Zurich, but it sounded cooler so I moved to Sweden in 2017,” says Reber.

First, the researchers built a facility for the alligators outside Vinslöv in northern Skåne, where the private owner had plans to build a new zoo. But when those plans fell through, Gudrun, Ivar, Toke, Sigi, Bestla and Kåra were moved to Ystad Zoo, where they also got more space.

Here, the reptiles live in a building where they have a pool that measures almost 100 square metres at their disposal and almost the same amount of dry land covered with sand and artificial grass, as well as a research area of around 60 square metres. The entire area is fenced with glass and a fine-mesh fence to mark the space where visitors to the zoo can pass. The air is warm and humid.

“It’s 27 degrees,” says Stephan Reber; “which is actually a bit cold for the alligators, but they can warm themselves under heat lamps and are doing fine. At warmer temperatures, it would also be easier for us to study them, because heat makes them more active.” The reason for limiting the temperature, he says, is the high electricity prices that make it harder for the zoo to manage financially.

Difficult to take care of

The facility was paid for by Lund University, which also funds the upkeep of the animals and takes responsibility for their care, with support from the researchers.

“Taking care of crocodilians is difficult. There are things you need to know about their diet and other needs. We contribute with our knowledge,” says Reber.

Mathias Osvath emphasises that the studies that the researchers do take place on the animals’ own terms. “We don’t even need ethical approval for the type of research we do. We don’t do anything with the animals that you aren’t allowed to do otherwise. We observe them and feed them. An extremely important basic principle is that the best animal protection is when the animals themselves choose what they want to do. Also, what they do must be of their own free will in order for us to get accurate results. When they interact with each other, they shouldn’t even notice that we’re there. So it’s completely different to working with lab mice and animals used for experimental purposes.”

One thing the researchers have learned is to be patient with the alligators.

“It takes much longer to do the same test with a crocodilian than with a bird. Alligators can’t eat as much at one time, because they are cold blooded.They are slower, and there is no existing research. So we have to put everything together ourselves. We have developed each step with the help of knowledge and experiments. I never thought I would become an alligator trainer, but now I am one,” says Reber.

For one test, he built a contraption with a different colour on each side. The alligators had to touch the right side to get food – something they proved able to do with flying colours.

“It took us six months to complete the data collection. It was hard work, but we found that all the alligators passed the test at the first attempt. They had never seen the device before and had never previously had to touch anything to get food. They made the connection very easily and it just worked.”

Did not take the food

Occasionally, the alligators chose the right side but then did not take the food. “That they were so eager to do the tests was surprising to us, and it shows that alligators are also playful,” says Reber, while backing away from Gudrun with the wooden stick in front of him.

The stick is a safety measure that the researchers always have with them when they enter the enclosure. Otherwise, nothing other than normal rubber boots is required. The safety aspect was also a reason why alligators were the first choice when Mathias Osvath was looking for crocodilians.

“Alligators are the easiest to work with,” he says. “They don’t want to eat you. Unlike Cuban crocodiles, for example. If you stick out an arm like that to one of those, you can count on it being taken. That’s what happened at Skansenakvariet. But alligators don’t do that.”

Not completely risk-free

“It’s never completely risk-free, but we wouldn’t get this close to them if it involved great danger,” adds Simon Grendeus, who applied to the group as a volunteer and is now a research assistant. He has a master’s degree in cognitive science but, unlike most of his colleagues, has never studied animal cognition. However, his philosophy and linguistics studies have proved useful in the work, and this autumn he will begin his doctoral studies.

“I have experience in the field of phonetics and can study which parts of words the alligators understand,” he says. “You don’t get many opportunities to work with alligators, and I like it. Even the more boring chores like cleaning, because it’s a much-needed break from sitting at the computer or reading.”

He has also changed his opinion about alligators.

“When you see them on TV, they don’t look very engaged or aware, but they are very aware, and that was a surprise to me.”

Surprising results

Mathias Osvath believes that many people will be surprised when the researchers start publishing the results of their studies, which he hopes will be soon. “People will probably be amazed by how much reptiles have going on in their heads, because no one has assessed these animals cognitively before.”

He says that at first, they chose simple tests in the belief that the alligators would not be able to manage very much, but they had to re-evaluate that opinion. “The alligators have abilities that children take a long time to develop. If you repeatedly hide something thing in one place and then switch to putting it somewhere else, small children tend to go to the first place even if they’ve seen everything happen. But the alligators learned quickly.”

Osvath talks about a hypothesis that the dinosaurs developed advanced cognition earlier than the mammals. “I think there may be a Copernican twist which shows that birds – and their non-flying ancestors – were the first to do most things and were followed by mammals, not the other way around as has been thought. Many results point in the same direction, even in neuroscience and palaeontology, so the shift is certainly possible. It’s fun to be alive right now!”

WHAT ARE YOU DOING HERE?

Thibault Boehly, doctoral candidate in cognitive science at Lund University.

“I’m studying the executive functions of alligators. For example, we hide food, and the alligators have to memorise and make the right choice to get it. I’ve never worked with alligators before, so it’s a learning curve.”

What is your background?

“I’m from France and have a bachelor’s degree in biology and a master’s degree in ethology from Strasbourg. Since then, I’ve worked at the Max Planck Institute, studied parrots on Tenerife and worked at the University of Vienna. I came to Lund University in September 2021.”

Why did you want to work with alligators?

“It wasn’t something I planned. But you don’t get many chances to work with alligators, so I just had to say yes.”

What do you think of Lund and Sweden?

“It’s nice. It’s better than many other places I’ve worked because I have more time and better pay. Sweden is a nice country to live in in general.”