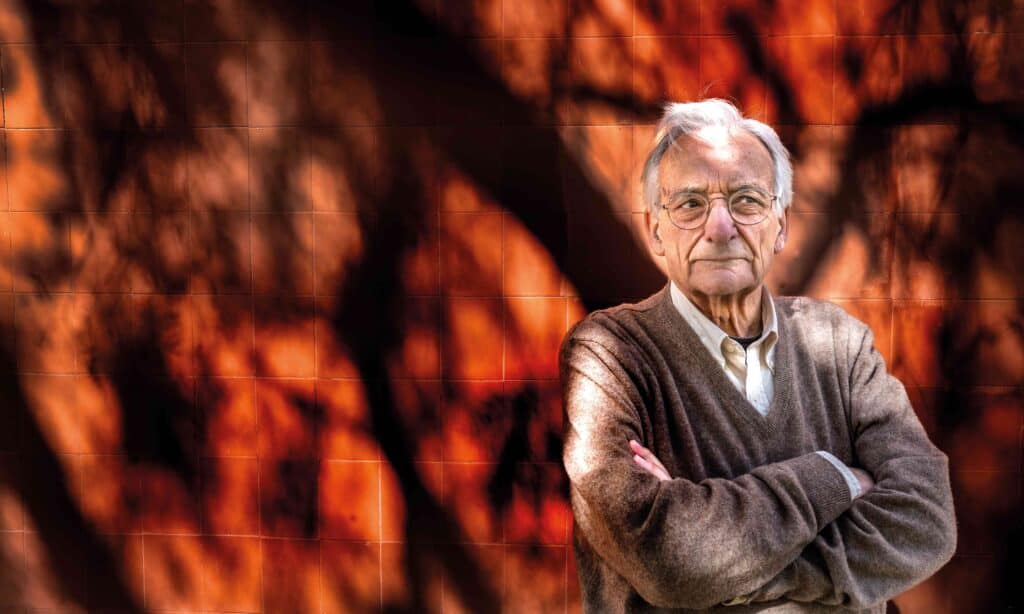

A tall woman walks briskly through the British Museum. She has just finished a music history lesson and wants to eat something before her next session.

“Today I have lessons in two completely different places. The quickest route is through the museum, and I can buy coffee and sandwiches here,” says Annika Lindskog.

She moved to London in 2001 to secure a coveted tenure-track position at University College London, UCL. Even then, there were few permanent positions for people who wanted to teach Swedish as a second language at university level.

“That’s why I’m still here,” she laughs. “I have nowhere else to go.”

Although what she says contains a grain of truth, she loves her work. The combination of teaching, researching and planning courses suits her perfectly. Lindskog teaches advanced Swedish, advanced Scandinavian translation, Nordic landscapes and a number of cultural history courses. This morning’s course, Music, Nations, Society is about classical music and national identity in Europe in the 19th century. It is connected to her own research.

When she started at UCL, the Scandinavian Department was its own department. There were separate courses in Swedish, Danish and Norwegian literature. Nowadays they offer a course in Scandinavian literature instead.

Lindskog explains that Brexit has impacted the Scandinavian department and its potential students.

“We have never had very many students, but previously we had more from other EU countries such as Poland, Germany and Romania.”

Nowadays, the Scandinavian Department is part of the School of European Languages, Cultures & Society, which includes four Nordic languages as well as Old Norse, French, Spanish, German, Italian, Dutch and Portuguese. Another change is that Annika Lindskog and her colleagues have chosen to develop courses in Nordic and thematic subjects within cultural history, literature, music, film and history.

“Actually, we should change the name to the Nordic* Department. That is a more accurate reflection of the countries we cover. In our introductory course for first-year students, we go through five countries and around 2,000 years in 20 weeks.”

Her book Introduction to Nordic Cultures, published in 2020, is linked to that course.

“The funny thing about the book is that it is based on a course where everyone in the department helps with the teaching.”

Each lesson is about a major event that happened in a certain year. Lindskog tells us about 1732, when Carl von Linné set out on his expedition to Lapland, and 1792, when King Gustav III was shot.

“The book is a kind of identity marker for us. It is the region that is most interesting, not the national perspective. But on the language courses we work nationally of course. We do not have a Finnish language course, but we include Finland in other courses.”

Finland is close to Annika Lindskog’s heart because her mother was born in the Finnish region of Ostrobothnia and her family spent their summers there. She herself grew up in Överkalix in the north of Sweden.

“That’s why I’m so good at northern dialects and Finnish Swedish,” she says, adding that her mother, who was also a teacher, is very interested in Swedish language and literature.

From her father, a church musician, she acquired an interest in music that has remained with her throughout her life.

“I attended the music high school in Skellefteå and spent a year at the Academy of Music in Piteå. But I also wanted to focus on Swedish.”

So Lindskog studied to become a school teacher of Swedish and German at Umeå University, and now she teaches Swedish and music from a cultural historical perspective. But how did she get from teaching schoolchildren to what she does today?

It started with an exchange year in Würzburg, Germany, where she took up an offer to teach Swedish to German students.

Lindskog remembers how she and fellow student Eva used to sit in the kitchen of their student residence, drink cheap red wine and plan their Swedish lessons in German, without the faintest idea of what they were doing.

“We had great fun and the students loved us, but I don’t think they learned very much Swedish.”

In Würzburg, she made friends with Germans and other exchange students. At one point, one of them, who was from the UK, said:

”I think they study Swedish with us because they usually run around with candles on their heads and white clothes once a year. Aha, thought Lindskog, you can teach Swedish at foreign universities.

“It sounded incredibly exciting to work with slightly older students who wanted to study Swedish. Much more fun than teaching reluctant 13-year-olds.”

So that is how the idea for Annika Lindskog’s future professional life was born. She finished her studies in Umeå while working at the opera house Norrlandsoperan for a year.

“Choir singing is still a big part of my life,” she says in her well-balanced alto voice with splashes of her northern Swedish accent.

At the time, Umeå University had a collaboration with Lampeter University in Wales, where Umeå sent assistants to teach Swedish. Lindskog managed to get one of those positions. Via the Swedish Institute, she then got a position at the University of Belgrade in 1996, in the midst of a raging war.

Somehow, they kept the teaching going, even though all normal activities ceased. The year in Belgrade gave her an understanding of what it is like to live in a troubled conflict zone.

“I carry with me memories of the people I met. One of them was a student called Jelena, who is now one of my colleagues.”

She then got another position through the Swedish Institute, at Dublin Trinity College. When a permanent position at UCL came up, she applied for it.

“At the time, there were full-time studies in Scandinavian subjects at five universities in Great Britain. Today, only we and Edinburgh University are left.”

Lindskog has worked out by herself how to break down the components of Swedish in order to then be able to teach the language. As a Swede abroad, she can relate to the challenges other nationalities face in learning a new language.

“My German was pretty poor when I went to Germany, and when I moved to Wales, I could barely speak English. But you learn.”

At the last census, she wrote English as ‘first language’. “Even though I speak the language fluently and have lived here for so long, and even though I even write my research about Swedish music in English, I’m never completely sure.”

Unlike in Swedish.

“I have full ownership of Swedish. It’s my language. I can’t make language mistakes in Swedish,” she says, and does not think she is being arrogant. “On the other hand, I don’t like it at all when you change the language,” she adds half-jokingly, and says that neither she nor her final year students recognised any words on the 2023 list of new words.

Lindskog hurries away to the day’s second class. The three students are in their fourth year on the Scandinavian programme and have just returned from an exchange year in Sweden.

With her students, Annika Lindskog talks about national identity and culture. What is identity and how is it formed?

For her, someone who has lived her entire adult working life abroad, the answer is not obvious.

“Can we talk about a Swedish identity? It is very difficult to generalise and say that all Swedes are like this or that,” she says, revealing that she was recently granted British citizenship. “Mostly so they can’t throw me out.”

Lindskog tells us that she, her colleagues and their students are used to not having to define themselves all the time. They’ve learned that things do not work that way.

“If you move somewhere else and live there, then that life also becomes part of your identity. What we really want to look at is the question of how we can understand a culture even though we cannot define it.”

With that, we return to her main motivator and purpose for teaching Scandinavian studies, a topic she believes is more important than ever now that the image of Sweden is often simplified and distorted in a negative way, with a focus on things like Koran burning, gang violence and a troubled NATO application.

“We have strong feelings about how relevant we think a nuanced and multifaceted picture of Sweden and other countries is. Actually, we do not want to convey a particular image of Sweden or any other country at all. We give our students tools to discover and understand phenomena in Sweden and other countries themselves.”

The first task the students of Swedish are given is to make a fictional podcast on the theme ‘typically Swedish’. It could be about Ikea or the right of public access, for example. They realise fairly soon that you cannot generalise, because even if certain behaviours are a little more pronounced in Swedish culture, it is much more subtle than that.

Lindskog thinks about whether the image of Sweden is actually a Swedish concept. If you go out into the world and ask about what people think about Sweden, you will not get a uniform picture. Other people are rarely as interested in Sweden as Swedes are.

One of the chapters in her book Introduction to Nordic Cultures is about stereotypes. She says that it makes sense to help students see beyond stereotypes, because the problem with stereotypes is that you believe something about something you know nothing about.

“When they learn to analyse, study, explain, talk about and critically examine another country’s language, culture, history, society and politics, they acquire an understanding of others, which enables them to understand themselves better. That understanding is extremely important for a harmonious planet.”

When the students complete their studies after four years, Annika Lindskog is proud that the world has young people like her students.

After Brexit, the UK was forced to leave the Erasmus programme. For the past two years, her School of European Languages, Cultures & Society has been trialling summer courses, as a kind of compensation for the loss of Erasmus.

“My colleague Jelena Calic and I created a course about Stockholm delivered in Stockholm, with a mix of historical and cultural studies. It was fun and dynamic because the students wanted to learn something about Stockholm. Not just about Vikings, which are otherwise our big draw.”

Lindskog’s own research is not about Vikings and it has nothing to do with her teaching of Swedish. It has increasingly come to be about how certain Swedish and Nordic music from the end of the 19th century to the early 20th century is characterised by a specific cultural-geographical place in relation to our cultural and national identity.

When thinking about her teaching and research, she is often in Sweden mentally, and she misses the February light in northern Sweden.

“The problem with living abroad is that there is always something you have to go without. Although there has been no reason for me not to stay here, says Annika Lindskog, but adds: “When the sun is shining, I feel guilty if I don’t go outside. I’m still very Swedish.”

*The Nordic region includes Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, including the self-governing territories of the Faroe Islands and Greenland, and Finland, including the self-governing territory of Åland. Scandinavia is part of the Nordic region and includes Sweden, Norway and Denmark. Sometimes Finland is also included in the definition. As a geographical area, Scandinavia refers only to the Scandinavian peninsula, i.e. Norway, Sweden and the most north-western part of Finland.

Source: The Swedish Institute for Language and Folklore.

About Annika Lindskog

Annika Lindskog researches and teaches Swedish and cultural history at University College London, UCL. She lives in a house in Winchester, an hour by train from London.

In her spare time she enjoys hiking, listening to music and choir singing, including in the Winchester Cathedral Chamber Choir. She previously sang with the BBC Symphony Chorus for 15 years.