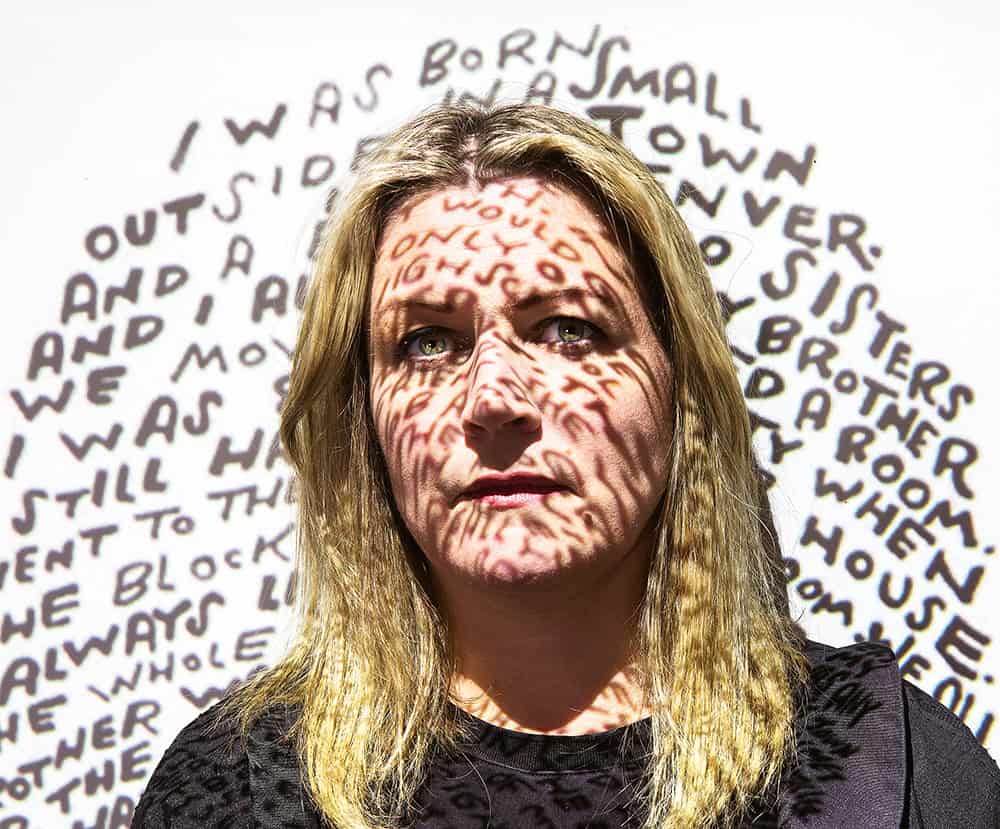

Sweden does not decide how the international situation changes, but we need a defence that develops and adapts in line with it, writes Oscar Jonsson, a researcher in war studies at the Swedish Defence University, in his latest book Försvaret av Sverige (The Defence of Sweden). About a year after it was published, he sits surrounded by shelves of neatly arranged books and portraits of soldiers and royals in a lounge at the Swedish Defence University. The rest of the building is not nearly so grand, he will remark a little later as we take the lift up to his office.

Jonsson is used to being interviewed. On his previous day at work – a Friday – he was in a studio at Swedish Radio answering questions about the recent drone incidents reported in Denmark, which closed down airports and prompted Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson to lend the country Swedish anti-drone systems. Then it was time for TV 4, where he was also asked about drones in Poland and Romania.

“What has happened is unusual,” he says. “The first incident, when drones were sent into Polish territory, is serious. Even if it turned out to be a decoy, to mislead. The Poles did not know that at the time, but it looked like 19 attack drones with 50 kilograms of explosives were sent deep into Polish territory. Obviously, that feels like a direct attack.”

Combined with another incident, where Russia violated Estonian and Polish airspace for 12 minutes, the situation is unique. Although violations of airspace occur regularly, they usually last for a very short time. In both cases, NATO’s Article 4, which states that the security of a NATO country is under threat, was invoked.

“That has only happened nine times in NATO’s history. Five of those were Turkey, one was the invasion of Ukraine in 2014, and one was the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. So a fifth of all the times that Article 4 has been invoked happened in those two weeks.”

The reason why Russia has started to act in this way, Jonsson believes, is to show that it can. It is also possible that they want to obtain intelligence information, for example on drone defence systems, or test how NATO countries’ policies respond to different types of attack.

“But if you zoom out a little, fear is the most important thing. Right now, Europe is talking about sending troops to Ukraine and confiscating Russian central bank assets. The only thing holding us in the West back is the fear of a Russian response. The fact that we are afraid is of great value to them.”

We should therefore make sure that Russia pays a price for its actions, he believes.

“It is relevant to ask ourselves the question of what price they pay if they do something. If the only cost is that we issue a strong statement that it is unacceptable, I think they will laugh and carry on. Different things need to be addressed in different ways.”

He gives the example, not too far back in time, of the damaged cables in the Baltic Sea.

“When that happened, NATO launched an operation, Baltic Sentry, where they took action in the Baltic. Some ships were prosecuted, and now there has been no more cable damage in the Baltic. I think it is the same with the drones.”

Jonsson is currently in the final stages of writing a book – an academic one this time – about the Russian General Staff, the most important military institution in Russia.

“I am trying to put together something of a standard work. What do they do? The history. The culture. How they influence policy.”

Somewhere in their upper twenties, people are selected for the General Staff’s own university. Those who make it through the first stage, known as the Combined Arms Academy, go on to the General Staff Academy. From there, the top 30 per cent are sent on to the highest positions in Russia’s armed forces.

The book is divided into three themes. Firstly, it deals with military leadership, how the General Staff manages operations and troops; secondly, the General Staff’s responsibility for developing military theory; and thirdly, how it is a key player in the interaction with Russian politics.

The second main track of his current research is on Russian lessons from the war in Ukraine, a war in which Russia – as Jonsson describes it – has two driving forces: regime security and major power status.

“Ukraine has twice had popular uprisings against autocracy, an economy controlled by the elite and arbitrary rule of law. And for democracy, free markets and Europe. I do not think the Russian leadership can allow Ukraine to succeed in those efforts.”

Oscar Jonsson’s path to becoming a researcher was not straightforward. After studying peace and conflict at university and a master’s degree at King’s College London, he became interested in Russian foreign and security policy. He started his doctorate, but he put it on hold for a job with the Swedish Armed Forces. He then moved to the United States to take it up again before the Swedish Defence University got in touch. At that time, the university was not authorised to grant a PhD, he explains.

“They did not call it a pretend doctoral programme, of course, but they employed people who were doing their doctorate somewhere else. Then they had supervisors and processes here to show the Swedish Higher Education Authority that ‘we are ready’ to be given the right to grant a PhD,” he says.

Jonsson completed his thesis in 2018, and his first job was a temporary position as a manager at a think tank. He then got a management position at a research centre in Madrid, where he moved in the middle of the pandemic. Between these jobs, he wrote a book based on his doctoral thesis, The Russian Understanding of War.

“When I looked at my diary for the week in those days, I realised that the things I enjoyed most were seminars I gave about the book sometimes in the afternoons or evenings. And that I really wanted to get back to the role of expert.”

He moved back to Sweden to take up a permanent position at the Swedish Defence University a month before Russia invaded Ukraine. That autumn, his book The Threat from Russia (Hotet från Ryssland) was published, followed two years later by The Defence of Sweden.

“I think academia has the unique ability to study things in depth, think critically and reflect on the issues. At the same time, it is also the practical aspects that are most interesting to me. It is great that I can combine these.”

At the time of writing, drone alarms are being sounded in Norway and flights are being diverted from Oslo’s Gardermoen airport. In Munich, air traffic has been halted for two nights in a row, affecting thousands of travellers.

On Swedish soil, a manager at the Swedish Defence Materiel Administration is interviewed in the business daily business newspaper Dagens Industri and assures the reporter that the Swedish people are safe. Everything possible is being done to keep up with developments in drone technology. Shortly afterwards, the Minister of Defence, Pål Jonson, announces a billion-kronor investment in more anti-drone systems.

Although drones at airports are ”pinpricks and provocations”, they are by no means unproblematic, says Jonsson.

“If you shut down Kastrup or Gardermoen for four hours, that has pretty big financial consequences.”

But he does not believe that Russia would see NATO as providing a real threat of attack. If they did, the Russians would not have emptied the border with Finland and the Baltic states.

“If they really believed that NATO was about to launch a military attack, they would not have done that. But the people who stand in Red Square with placards saying ‘maybe we should try a bit of democracy’, I would say they are among the most serious threats to the Russian leadership.”

A series of events in Georgia, Ukraine and Belarus, but also the Arab Spring, are part of that development. Ukraine is quite simply a threat to Russian regime security, he continues.

“Russia wants to have influence in its neighbouring countries and feels insecure if it does not have control and buffer states. For historical reasons, Ukraine is particularly important to them.”

Russia tried to gain control of Ukraine by non-military means first, during the presidency of Viktor Yanukovych and then with the annexation of Crimea in 2014. With each passing year, Russians perceived Ukraine as more stable, democratic and integrated with the West. Time was running out, and the only option that remained was a full-scale invasion, says Jonsson.

How the war will end, however, is a question he would rather avoid.

“Not to be boring, but I do not think it can be answered. But when it has happened, I will be able to tell you why it happened.”

Then he thinks about what he has said:

“That was a boring answer, but it all depends on what the outside world does.”

The current balance of power between Ukraine and Russia is clear, he says. But if the EU seizes Russian central bank assets or if US President Donald Trump takes a hard line, then the situation will be different.

“I think that by far the biggest question mark is the United States. Whether or not they are prepared to put any kind of real pressure on Russia.”

There are also question marks surrounding Russia’s economy, although Jonsson finds it difficult to see that this would affect the country’s military capacity in the short term.

“They prioritise that regardless. To put it into context, they spent 10.6 trillion roubles on defence and security last year, and they have spent 13.2 trillion roubles, or about 45 per cent of the state budget, this year. Meanwhile, cuts are being made to health, education, social care, higher education and research budgets.”

He does not believe there will be an immediate economic collapse in Russia.

“But what they are doing in the medium term is damaging a lot of the things you want to have in a healthy economy.”

So it is in line with this international situation that Sweden needs to develop its defence capabilities, to return to the theme of our opening paragraph. And there is plenty to do, Jonsson believes. Right now, Sweden is building the defence forces that were needed before 2022.

“We are doing pretty much what we always do. Buying expensive platforms in small numbers that take a long time to deliver.”

What has happened in the war in Ukraine is that relatively cheap weaponised drones communicate with each other in connected information systems. Sweden is at a high level when it comes to technology, but on too small a scale. What is missing is a good mix, he says.

“You need a highly competent core, and we are building that. But you also need to have a larger mass that complements that core in order to be relevant in modern warfare.”

He also describes how Russia is building a defence that aims to undermine the ideological attractiveness of the West, which makes the threat broader.

“There are lots of things we need to do militarily, but there are also many other things. Our open economic system, our open information domains, cyber security. We need to have a holistic approach to it,” says Oscar Jonsson.

Researching Russian warfare

Oscar Jonsson has a PhD in War Studies from Kings College London. His research focus includes Russia, Russian warfare and AI.

He is currently studying what Russia has learnt from the war in Ukraine. He is also writing an academic book on the Russian General Staff, scheduled for publication in spring 2026.

He is the author of three books. The Russian Understanding of War: blurring the lines between war and peace (2019), based on his PhD thesis; Hotet från Ryssland (The Threat from Russia, 2023); and Försvaret av Sverige (The Defence of Sweden, 2024), which won the Stora fackbokspriset, Sweden’s biggest literary prize for non-fiction, in 2025.

Oscar Jonsson …

… is a researcher in war studies at the Swedish Defence University. In his spare time, he enjoys reading, working out and climbing, although an injury is currently preventing the latter.

He likes to read several books at the same time, and he is currently reading Gisslan in Iran (Hostage in Iran) by Johan Floderus. On his bedside table is The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa.

Oscar Jonsson has a partner, a child and a small cottage in the county of Västmanland, where he chops wood, makes fires and spends time enjoying the nature.