Lisa Kaati greets Universitetsläraren in the foyer of the large rectangular building in Kista, north of Stockholm, which houses the Department of Computer and Systems Sciences at Stockholm University, where she teaches and researches cybersecurity. Part of this involves toxic language on the internet, a term used to describe communication that poisons the dialogue climate on social media.

This might be incitement to racial hatred and defamation, but also other forms of language, such as derogatory terms, invasion of privacy or disrespectful comments, she explains.

“The kinds of thing that make people not want to participate in the discussions. In political discussions, for example, there can be quite a harsh climate, but what we analyse is when people make personal attacks or talk about irrelevant things, such as derogatory comments about people’s intellectual capacity or appearance, when discussions should really be about the person’s work.”

In another area of her research, she tries to identify risk or warning signals in people who are prone to violent behaviour.

“There, we don’t analyse toxic language but try to identify actual threats or someone describing a planned violent act. We also analyse psychological factors in individuals. Is this person expressing a perceived injustice?”

Several warning signals found together can indicate an increased risk that a person will actually commit a violent act, she explains, adding that many people use offensive language online, but far from all are willing to commit violent offences.

Kaati’s research career began with doctoral studies in theoretical computer science at Uppsala University. With her new PhD qualification, she applied for and was offered a research position at the Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI). She points out her former workplace through the window, just a couple of hundred metres away.

“I thought it sounded exciting. I think I’ve always been a little interested in government work and helping to create a safer and better world. It’s kind of a driving force for me.”

Shortly after she started at FOI, the Utøya terrorist attack took place in Norway. There was a lot of talk about how to prevent similar incidents from happening again.

“That was when I started doing research on trying to identify potential perpetrators of violence by collecting various clues that people leave online. Looking for this kind of thing on the internet was quite new at the time.”

She continued working with this during her 14 years at FOI. As a data scientist, she developed tools to support analysts in their work to sort through the huge amounts of information.

“It is not possible to sit and read everything that is written on the web. You need to sort through it. Computers can never replace people and their analytical skills, but we can help filter out what people need to read and understand.”

She describes her work as “extremely interdisciplinary”. She collaborates with specialists in other areas, such as psychologists, political scientists and criminologists. Her own role is to create methods to analyse large amounts of data to identify different kinds of signal. And she says she is pretty much alone in her approach to that work.

“There are some researchers in other countries doing similar things, but maybe slightly differently. And not many of them come from my field, computer science. This is more of a problem that people with social science backgrounds work on. So in that way I probably have a slightly different approach. My starting point is technology. I don’t need to use other people’s methods to analyse data; I can develop my own.”

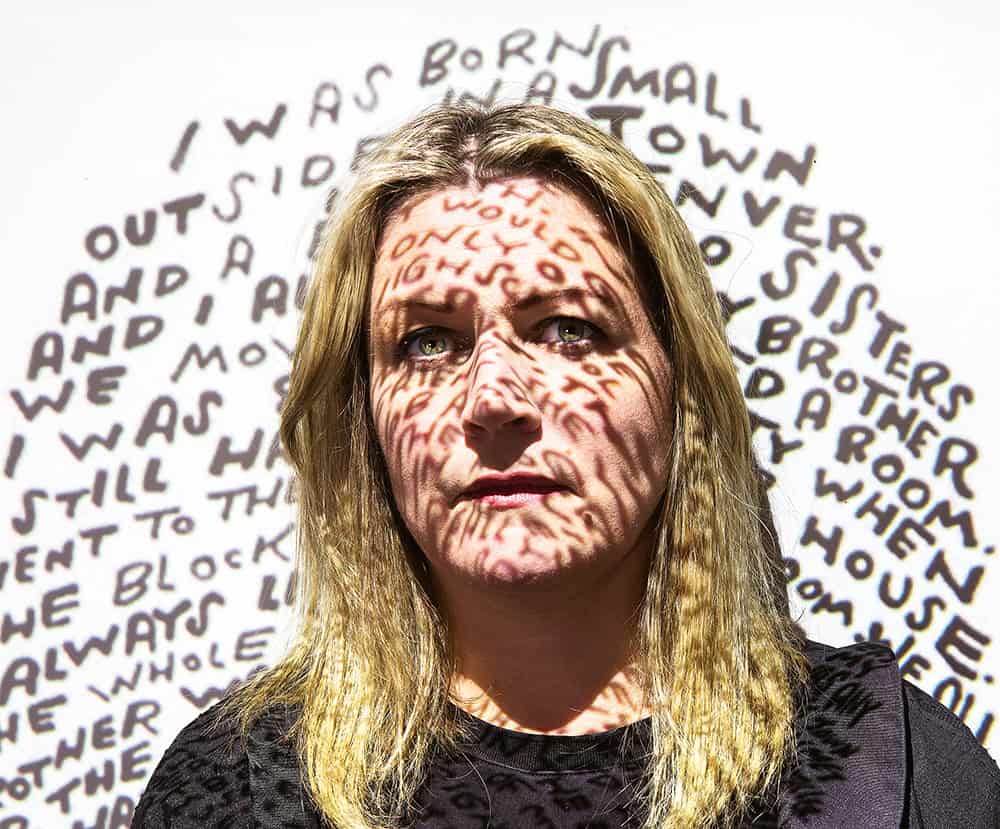

At FOI, Kaati ran a research group that mainly worked on different government assignments. These included studies of violent extremism and online hate and threats. This work meant that Lisa Kaati herself was subjected to hate and threatening comments in various online forums. She shows a picture with a handful of quotes about her: “That stupid bottle-blonde feminist witch,” “She’s a Jew-loving left-wing extremist” and “Why is she speaking out? She’s weak-minded” are just some of the comments.

She describes the personalised hatred as the hardest part of her job.

“During certain periods of my life, I have actually found it very difficult when people comment about me. That I’m a “scientist” in quotation marks, or that I’m a diversity pick, or comments about my husband’s ethnicity and religion. I’ve been called a Jihad Jane who is trying to Islamise the Swedish Armed Forces.”

She says she has periodically been afraid to answer the phone, especially when she worked at FOI.

“Nowadays, I’m probably regarded more as a boring scientist like any other. My opinions are my own. But when I worked at FOI, even though I felt I had the same role as I have now, there were still other people who saw me as a representative of the government or the Swedish Armed Forces. Even though that’s not the case just because you’re a researcher at FOI.”

Although she has advised politicians on how to deal with online hate, she hasn’t felt confident about what to do when it happens to her. “My colleagues and I have been very supportive of each other, so that no one has to sit alone and read everything written about them.”

Three years ago, Kaati moved from FOI to Stockholm University. It was a major change to go from a pure research position to teaching 70 per cent of her working time.

“It’s great fun,” she says. “I’ve also had the luxury of creating my own courses that are closely connected to my research on how to conduct online intelligence analysis and analyse large amounts of data.”

She describes university work as freer, something she initially found difficult.

“At FOI, I felt that the managers wanted to keep an eye on things and make sure that everyone was at the office. When I came to the university, it was a huge change for me that nobody really cared when or where I did my work, just that it got done.”

As a teacher, she also faces challenges in the form of cultural clashes. She says she has had students from other countries who do not know who Hitler was.

“How can I explain anti-Semitic stereotypes to someone who has no idea about the Second World War or Hitler?”

The first time it happened, she was taken aback and did not know where to begin an explanation.

“It started with us looking at anti-Semitic stereotypes. We had a lot of images for the students to discuss. Young people in Europe today are so well aware of what you can and cannot say and how to express yourself. Students from other parts of the world could say “there’s an old man in the picture”, even though it was one of the most well-known anti-Semitic stereotypes that you think everyone should know.

She still finds it difficult to explain things like this, things that people in Sweden take for granted, but says it is useful for her.

“It makes you realise that the world looks so very different.”

This summer, Kaati was on an exchange programme at Boston University, where she has started a collaboration with an American researcher. In the USA, threat assessment is a larger field than in Sweden, and there are more analysts working to identify and assess individuals with a heightened risk of committing acts of violence.

“The aim of the project we were working on was to try to separate people who make threats from those who actually pose a threat. We had taken texts from various internet forums with extremely threatening texts, which analysts in the USA then read and assessed by answering questions about whether this was a person that should be investigated further or just someone talking.”

So far, the collaboration has resulted in two joint articles and a co-operation with the FBI.

“The FBI’s Behaviour Analysis Unit is the same unit you often see portrayed in TV shows chasing mass murderers and serial killers, which makes working with them a bit more exciting. Their analysts are leading experts in threat assessment, and now they will be working with us to analyse and assess texts.”

So how is the dream of contributing to a better society going? Has she fulfilled it?

“My big problem when I worked at FOI was that no matter how many good things we did, the police authorities, (in Sweden and abroad, editor’s comment), could not use software that was a research prototype. They need to buy a tried and tested tool. So a few years ago, some of my colleagues and I started a company, where we are now trying to productise a lot of the things that we have developed in our research, with the hope that someone will actually be able to use them.”

She says most of the company’s customers are currently in the USA, mainly schools and police forces that use the tool.

“We received help from the incubation centre at Uppsala University, where my colleague works, and we have also been part of an accelerator programme. So we have had support and help all the way.”

In her research, Kaati is currently involved in a project together with the Swedish Gender Equality Agency to map sites that market sexual services on the internet. For example, they are analysing reviews written by buyers and profiles of the people selling sexual services.

“You could say that my research is about all the dark sides of the internet. I find it interesting to study everything that is bad about the internet.”

How do you cope with all the darkness and hate?

“You get used to it over time. When I started at FOI, one of my first projects was to analyse IS propaganda. At the time, many people wondered why people from all over Europe would choose to join a caliphate.”

She agreed to study the texts, but not the pictures of people being subjected to violence, or she would not have been able to sleep afterwards, she says. After a while, the images were less difficult to cope with, but she still refused to watch the films.

“After a few years, the films weren’t a problem either. You simply become numbed to it over time.”

A key motivator in that context is that the work needs to be done.

“I look at it like this: If we don’t do it, who will? It is extremely important to carry out this analysis to increase our knowledge of different phenomena.”

On the IVA 100 list

Lisa Kaati developed the Hatescan software program, which recognises toxic language in Swedish.

In 2023, Hatescan was included in the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences’ (IVA) 100 list of “current research with the potential to create value”.

Her tool is now being developed further by the company Mind Intelligence Lab, which Kaati runs together with research colleagues alongside her work at Stockholm University.

Lisa Kaati …

… is a docent and senior lecturer in cybersecurity at the Department of Computer and Systems Sciences at Stockholm University.

She focuses on analysing the presence and content of violent extremist messages online, developing technology and methodologies for threat and risk assessment in digital environments, and detecting hate and threats.

In her teaching, students analyse real data, which can often consist of extremely hateful language.