University West is just a brisk walk from Trollhättan Central Station. Visitors are greeted by the slogan “Creating change together”, inside the main entrance. A few days into the first week of the autumn term, this is perhaps more apt than ever. The change is noticeable not only to new students but also – or perhaps primarily – to employees.

In a few weeks, another part of the premises will be ready, having been converted into flexible office space. The departments of health and engineering, together with the university administration and the library, will be moving in. The change is part of a longer ‘soap opera’, explains Tobias Arvemo, chair of the local SULF and Saco-S associations at University West.

As an employee at the Department of Economics and IT, the plan was for him and his colleagues to move into flexible office space too. However, that part of the renovation has been put on hold, and he remains in his own office.

“So I am not a victim,” he says. Half-jokingly, half-seriously.

University West has financial problems. As recently as this spring, 29 employees were made redundant because around SEK 40 million needed to be saved, as Universitetsläraren has previously reported.

“In the current situation, it would probably be better to put every penny we have left into teaching and research rather than redesigning workspace,” says Arvemo.

One person who is “a victim”, i.e. who will be moving into a flex office, is Christina Karlsson, a lecturer in nursing and vice chair of the local SULF and Saco-S associations. These first weeks of the term will be particularly chaotic, because half of the new premises are not finished yet, she says. The temporary spaces that she and her colleagues have been using until recently have been cleared of furniture, as they are to be moved to the new office space. For now, they are sharing the flex offices that were completed earlier with the people who are actually supposed to work there.

“We just have to accept the situation as it is. During this interim period, there have been quite big problems, and a sense of homelessness,” she says.

The union has become aware during this process that there is concern among employees when it comes to the flex offices. Not having a designated desk will probably work fine for many people. For others, especially researchers and university teachers, it will not work so well.

Nevertheless, Karlsson is cautiously positive and points out that she welcomes the renovation. Hopefully, it will not become too crowded, she thinks.

“The concern is more about the need to be able to concentrate. I myself cannot do that in a large room with lots of other people. And I don’t want to assess students in front of everyone else, for example, because it is not fair to the students that other people can see and hear what I am saying. Yes, we wear headphones, but still…”

The two union representatives lead the way through the corridor in the new flexible office space. Karlsson leans against a row of personal lockers, which also seem to be able to function as desks. Susanna Höglund Arveklev and Frida Sjöberg are chatting at one end. Most of the lockers are empty at the moment. But soon, employees will have their own numbered lockers to store work materials and personal items.

Both Christina Karlsson and Tobias Arvemo emphasise that there is no dispute with the employer. The staff have learned to accept the situation. In the long term, however, neither of them can really see how flexible offices can be reconciled with the employer’s desire for employees to spend more time at work. Instead, there will be an increase in remote working, says Arvemo.

“As in many other places, working from home has increased since the pandemic. People have discovered its benefits; I myself save two hours and twenty minutes in travel time if I work from home. Now they have started talking about wanting people back at the workplace again. Doing this kind of renovation doesn’t seem like the smartest way to achieve that.”

According to Rickard Norén, Deputy Director of University West, they have a vision of a more vibrant campus in the future. With more teaching and more staff and students on site.

“We work hard to make our environments pleasant to spend time in and to ensure that they boost energy and provide added value. I think we have achieved that so far. It is more attractive to come in. It is a bit livelier, and it is a bit brighter,” he says.

Rickard Norén

Deputy Director, University West Foto: Kent Eng

However, he emphasises that stricter rules on remote working are not currently on the agenda. He does not describe the second stage of the renovation as being on hold. According to the current plan, the first stage will be evaluated before moving on to the next.

“I believe that the second stage will happen in some way and in some form. But we do not yet know exactly when or how,” he says.

Norén points out that University West has already saved money through the changes made so far. Some rental contracts have been terminated, resulting in lower rents.

“I think the figure is around 2 million per year,” he says.

Activity-based, flex or clean desk – what’s the difference?

A flex office, or flexible office, means that people have no fixed permanent workspaces. People who work in such offices choose a new place every day.

An activity-based office is divided into zones. Each zone is intended for different types of work, such as phone calls and meetings or quiet work and concentration.

The clean desk concept means that workspaces shared with others, such as desks, are to be cleared at the end of the day.

The Mälardalen University campus in Västerås is also undergoing extensive renovation. An adjacent building previously rented by another organisation, known as the S house, will be converted into flexible workspaces for support functions next year. Parts of the teacher training programme may also be moved here. The change will definitely lead to an increase in remote working, says Michaël Le Duc, a senior lecturer in business administration and the health and safety representative at Mälardalen University. He was also previously chair of the local SULF association.

The activity-based premises at Mälardalen University in Eskilstuna were completed just as the pandemic was becoming serious. By the time the corona virus restrictions were eased and it was time to move in, people had become accustomed to remote working. Many saw no reason to start working in the flexible office with no proper place to work.

“That is my interpretation,” says Le Duc. “People accepted the situation and started working remotely more often. I have understood that people here in Västerås feel the same way. You do not know where to put your books, papers, ornaments or photographs of your children.”

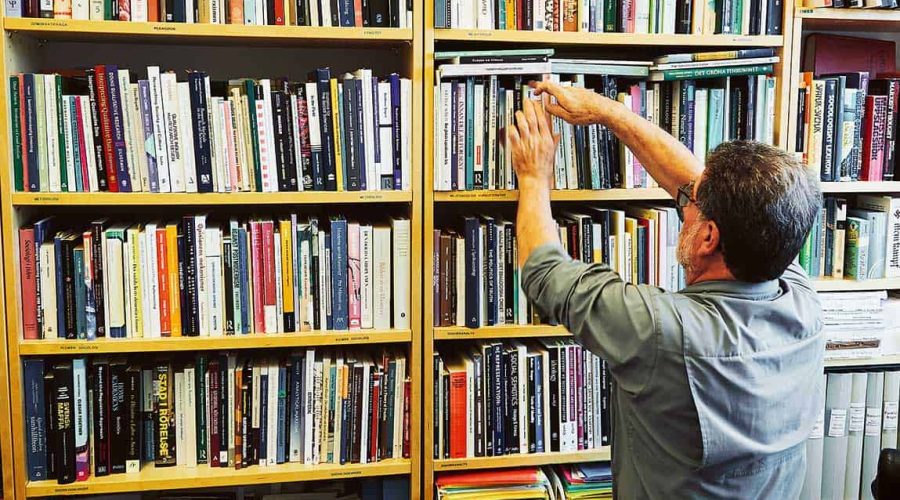

In his cluttered office, Eduardo Medina, a senior lecturer in sociology and the chief health and safety representative at Mälardalen University, is sorting books into boxes. He is due to retire in February, and it is time for him to start packing. After almost fifteen years as chief health and safety representative, he has been involved in the entire flexible offices process. He describes it as a long hard struggle.

Medina sees it as something of a class issue. Employees work from home on different terms, he says.

“That is how it is. Those who can afford it can have their own study at home. Older people like us, who don’t have children at home and live more modestly, can have a study at home. It is more difficult for those who sit at their kitchen table and work. You have to tidy up first before you can put your computer on the table.”

Eduardo Medina

Safety representative, Mälardalen University Foto: Mats Erlandsson

Knowing how things turned out in Eskilstuna, he also describes it as a given that remote working will increase after autumn 2026, when the flex offices are due to be completed. Based on the reactions he has received over the years, he believes that few people actually want flexibility.

“Those who do not like working that way obviously go into work less often because they can.”

Outside one of the glass doors to building S in Västerås, Carl-Mikael Teglund, a doctoral student in history didactics and a doctoral candidate representative on the local SULF association board, stops. Unauthorised persons are not allowed to enter, as clearly stated on a taped-up sign. It is late afternoon, and the building workers have left for the day.

The doctoral students at Mälardalen University have tried to communicate to their employer their wish to have access to their own room where doctoral students can sit together, he says.

“We don’t think that is too much to ask, but no one in a position of authority is sympathetic to our request.”

It is the middle of the first week after the holidays on campus in Västerås. Students will not start until next week, and it is considerably less crowded than normal, says Lisa Salmonsson, a senior lecturer in sociology and chair of the local SULF association at Mälardalen University. As she understands it, the renovation is about making more efficient use of space. At least to some extent.

“This is a workplace that many people travel to,” she says. “And the teaching agreement gives you quite a lot of flexibility in terms of where you work, unless you are teaching. In addition, we teach at two different locations. If you teach in Eskilstuna but have your office in Västerås, you may not be here at all that week.”

She explains – based on evaluations carried out among staff in Eskilstuna – that different professional groups have different feelings about the flex offices. Administrative staff and, to some extent, managers tend to be happier than those who work in teaching and research. “People want it to be more tailored to their needs. Teaching staff have a greater need for space where they can concentrate. To be able to mark students’ work and have piles of paperwork.”

Personally, she is positive about flex offices.

“But as a union representative for lecturers and researchers, it is obvious that they need to be able to shut themselves away. And that people do not want to have to put everything away every day and then get it all back out again the next day.”

She believes that many people already work remotely a couple of days a week. There is definitely a risk that this will increase as flexible offices become more common. However, she does not think that the change will necessarily be as great in Västerås as in Eskilstuna.

“Eskilstuna was supposed to open just as covid hit. No one had really been using it as a working space; that only started happening after the pandemic. By then, people had learned to work from home, which made it particularly unfortunate.”

If the activity-based premises had been opened sooner, it would have been possible to adapt more as time passed. Now, the step to working from home was not as big when the open plan office did not feel perfect, says Salmonsson.

“Now we are in a better position to try to do this in a more needs-based way.”

In principle, all employees will eventually work in flexible offices, according to Peter Liljenstolpe, Campus Manager at Mälardalen University.

“The campus plan approved by the board states that the aim is for most workspaces to be flexible, and that time frame extends to 2030. So my educated guess is that by 2030, basically all, or most, workspaces will be flexible,” he says.

Peter Liljenstolpe

Campus Manager, Mälardalen University Foto: Melina Hägglund

The premises should be seen as a shared resource to be used in a sustainable and efficient way, he explains. Peter Liljenstolpe cannot say exactly how much money will be saved.

“That’s impossible. What we can say is that we do not want to have higher costs for premises. And since we know that there are rooms that are not being used, it makes sense to work together in the space that is available.”

Right now, they are looking at how Eskilstuna’s rules for flexible workplaces can be adapted to the premises in Västerås. The basic idea is that there should be no personal workspaces and that an empty workspace should be available for anyone to use. However, there is nothing to stop people from sitting at the same desk every day. But they should not be able to store books or other materials there.

“The basic rule is that you do not do it overnight, but if you use the same desk for a whole working day, you can of course leave your things there for the whole day,” says Liljenstolpe.

On the other hand, anyone who needs a permanent space for medical reasons should be able to have one, he adds.

Tobias Arvemo and Christina Karlsson sink into blue-grey armchairs with sound-absorbing walls. They also believe that a well-thought-out rulebook is essential for flex offices to work.

“The rules we set for these environments will be very important for how they work,” says Arvemo. “But the employer needs to be responsive. If we identify problems, we will have to adjust the rules.”

He believes that the worst thing about flex offices will probably be the availability of space.

“It could be a challenge, especially for work that requires concentration. If you do work that does not require that much concentration, I think you will always be able to find space to work.”

For now, Karlsson thinks that the uncertainty is the hardest part. It is difficult to plan your work when you’re floating around and do not know where you will be able to sit all day. At the same time, the best thing about the new premises weighs quite heavily on the other side of the scales.

“It is nice to work somewhere that is clean and modern,” she says. “Absolutely!”

Flexible offices at higher education institutions

Universitetsläraren asked 35 HE institutions whether they have activity-based offices, and if so, to what extent. Of the 26 that responded, 12 reported that they have activity-based premises or flex offices to varying extents.

Halmstad University and Uppsala University stated that 1 to 2 per cent of their staff work in such premises. In Uppsala, only administrative staff work in this way.

Chalmers replied that 40 per cent of staff in its support functions work in such environments.

At Mälardalen University, 45 per cent of all staff work in this type of office. Their aim is that everyone will do so by around 2030. At University West, the proportion is 66 per cent of all staff.

Some HE institutions, including Malmö University and KI, reported that they are investigating the introduction of flexible premises in the future.