The past few years have been tough for Queen’s University Belfast (QUB), Northern Ireland’s largest university. In autumn 2024, the management announced that the institution’s financial deficit meant that 270 jobs needed to be cut. This process was then implemented during the spring, by offering a voluntary redundancy package to all employees.

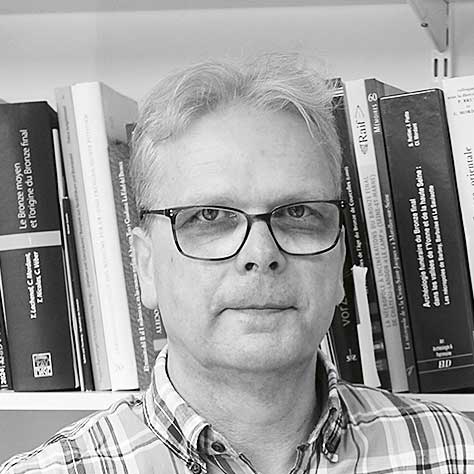

Dirk Brandherm is the head of geography and archaeology at QUB and a representative of the British trade union for university employees. He tells Universtitetsläraren that many of the staff who accepted the redundancy package were happy with the offer, but that does not mean that everything in the garden is rosy.

“The biggest question is how much workloads will increase for the remaining staff. There has been no systematic investigation into this aspect. And since most of the people who left did not do so until the end of July, the effects will not be felt until the autumn.”

Dirk Brandherm

Representative of the British trade union for university employees, QUB

QUB is not the only higher education institution in Northern Ireland with financial problems. The region’s state funding for higher education is limited – most of the budget goes to healthcare and school education – and tuition fees, which are capped at a level set by politicians, are less than half those in England. In early May, the three Northern Irish universities wrote an open letter to the regional government in Stormont asking for the cap on tuition fees to be raised, something Brandherm is ambivalent about.

“We are happy that we have lower tuition fees, even though this places some constraints on the university’s finances. However, we and the university are in complete agreement that more public funding is needed.”

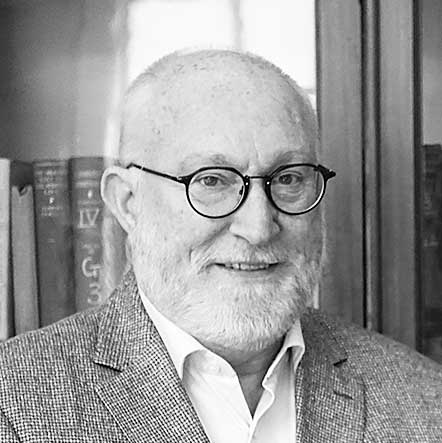

The demand quickly gained support from the business community and other higher education institutions. One of the people behind the letter is Peter Finn, vice-chancellor of St Mary’s University College.

“Even though we are actually competitors to some extent, the situation is serious enough to warrant us joining forces and speaking with one voice,” he says.

“But I want to make it clear that none of us took this decision lightly. Suggesting raising tuition fees was really a last resort, as all other avenues for increased funding have been blocked.”

Peter Finn

Vice-chancellor of St Mary's University College.

The universities’ request was rejected by the Minister for the Economy in Northern Ireland, Caoimhe Archibald, who cited the need for a funding system that remains affordable for students. However, she acknowledged that the situation is unsustainable and promised an investigation into an alternative funding model.

“I can understand why she did not agree to increased tuition fees, as it is a very sensitive issue,” says Finn. “She did not have the support of the opposition parties on the matter and chose to say no.”

He believes that the situation is a result of several factors. As with tuition fees, politicians have set a maximum number of student places that higher education institutions can offer, which means that many Northern Irish people choose to study in other parts of the UK. International students, who pay significantly higher tuition fees, have also declined in number in recent years.

The UK’s relationship with the EU is another factor.

“Ultimately, access to public funding reflects the strength of the British economy,” Finn continues. “And we all know that, financially, leaving the EU was not a smart move. The prospects for the British economy do not look bright for the next six or seven years, and to some extent this is due to Brexit.”

“There is not much hope right now. Each university can find its own ways to improve efficiency and get around the problem. But what is needed is a macro solution. We need more money.”