The changes to the law that came into force on 20 July this year primarily mean stricter requirements regarding financial self-support, which make it much more difficult for foreign doctoral candidates and researchers who want to stay in Sweden long term, (see Universitetsläraren, 23 August).

Universitetsläraren has talked to several doctoral students who have been impacted by the new law. One of them is Masoud Nouripayam from Iran, who is a doctoral candidate in integrated electronic systems in Lund.

“I was going to apply for a permanent residence permit in a few months, but after the law change I can’t, because I can only get short-term jobs,” he says.

He has been in Sweden for more than eleven years. He moved here in 2010 and studied at bachelor level, took a master’s degree and began his doctorate in 2018. Under the old rules, he could apply for a permanent residence permit after four years of doctoral studies. But now his plans have been turned upside down.

“With the new requirements regarding permanent residence permits, I must have 18 months of employment, counting from the time that my application is assessed. If I want to continue in higher education, I will only be offered short-term employment to begin with. If I take a job in the corporate sector, I will be given a six-month probationary period. This means that I will not be able to fulfil this condition.”

He is looking at various hypothetical situations in the future. “But my fear is that it will take so long that my doctoral studies will be too far back in time to be counted as a basis for qualifying for a permanent residence permit,” says Nouripayam. “There is absolutely no certainty about how and when I will be able to apply.”

“A lose-lose situation”

He is one of the founders of a Facebook group with over 1,200 members trying to bring about a change in the law. “We started the group when we found out about the new requirements in the law,” he says. “We are trying to inform as many doctoral candidates and researchers as possible and also trying to draw other people’s attention to the issue.”

He says that the group has received a lot of support in articles and public statements. “But something that I and other doctoral candidates are disappointed and frustrated about is that so far there is deep silence from the managements of universities, with the exception of Karolinska Institutet. Many of us believe that universities should show solidarity with us. This is a lose-lose situation. It is not just us doctoral candidates who are the losers, but also the entire higher education sector in Sweden. A lot of us doctoral candidates are now talking about whether we should perhaps leave the country. It feels like they don’t want us here.”

Preparing a letter to the government

Universitetsläraren asked the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions, SUHF, about what it is doing.

“Our expert group on employers’ issues is preparing a letter to the government on the matter,” says Marita Hilliges, the Secretary General of SUHF, “probably together with SUHF’s expert group on internationalisation issues, which is also concerned about it.”

“We shouldn’t have to be worried”

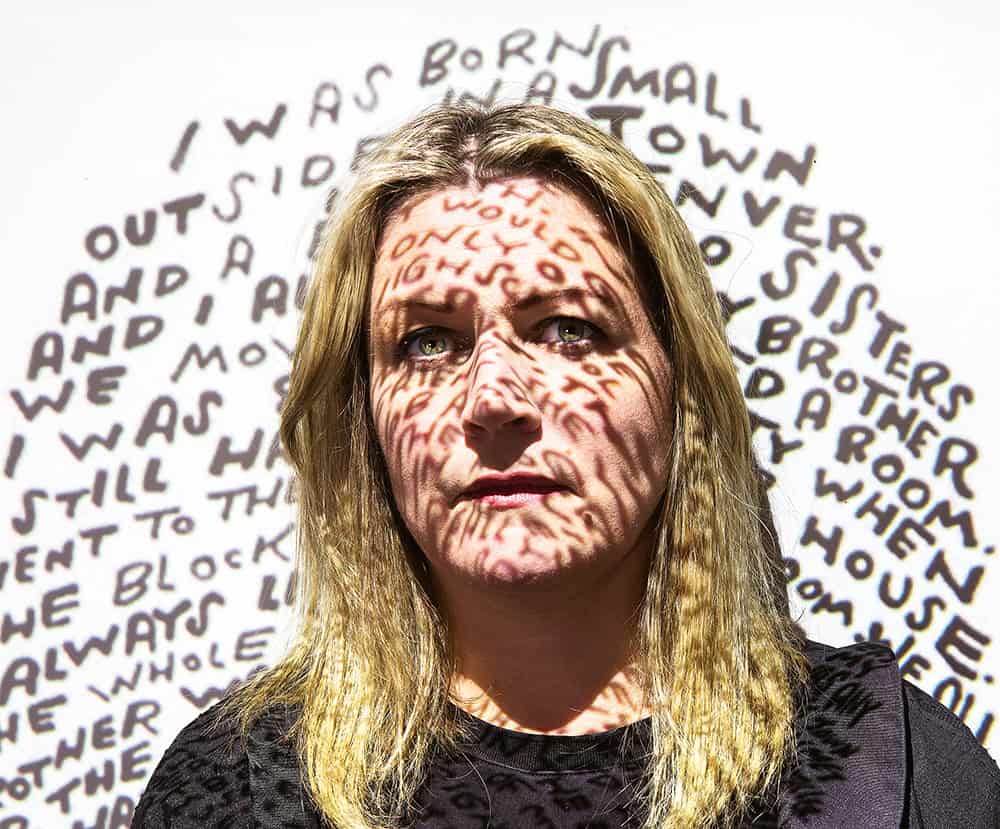

Sandra Donnally, from the United States, is a doctoral candidate in economics in Lund. She came to Sweden in 2015 to do a master’s and then started her doctorate in 2017.

“Because of the rule that residence permits for master’s studies don’t count,” she says, “I wasn’t able to apply for a permanent residence permit until I had been living in Sweden for six years. So I applied for a permanent residence permit earlier this year and discovered that the government had changed the rules.”

Now Sandra Donnally does not know whether she can get a permanent residence permit. “For those of us who are affected now, it’s really stressful. This is the worst time in the doctoral studies period that it could happen. We are in the process of completing our studies and need to concentrate on our thesis. We shouldn’t have to be worried about where we’re going to live, how we’re going to live and whether we might need to leave the country to apply for a new residence permit. It’s extremely stressful.”

“Nobody in higher education can meet the requirement”

She believes that the Swedish Migration Agency’s requirement for, in practice, guaranteed employment 18 months from when the application is assessed is extreme.

“This is a requirement that nobody working in higher education can meet. Basically, it means that doctoral candidates can never qualify for permanent residence until they have completed their doctoral programme and, in most cases, got a permanent job in the private sector.”

“I understand that the government has changed the law to in an attempt to stop losing voters to the Sweden Democrats, but this change in the law is not well thought out and it really impacts doctoral candidates, and probably other people as well, very negatively,” says Donnally.

She hopes that the Swedish government, or any of the various bodies that have drawn attention to the problem, will do something about the situation that has arisen.

Desperate, disappointed and angry

The SULF Doctoral Candidate Association, SDF, is deeply engaged in this issue.

“We want the law to be changed back to the way it was before July 2021, or for there to be an exception for doctoral candidates,” says Jennifer Emsfors, a member of the board of SDF and a doctoral candidate in business administration in Lund and Kristianstad.

SDF has had a lot of reaction from appalled doctoral candidates. “There is a lot of anxiety,” says Emsfors. “Many people are desperate. They are disappointed and angry. Some have been forced to take sick leave. Most people are very disappointed that they came here under the impression that they would be able to stay in Sweden, and they have counted on the change in the law that came into force in 2014 continuing to apply. Many have planned a future in Sweden and have families, children and homes here. Now they don’t know what will happen. In addition, the anxiety is affecting their ongoing doctoral work.”

She believes that the new amendment to the Aliens Act will have major personal consequences in the short term for the doctoral candidates affected.

“Collaborations and projects are also in danger of being negatively impacted, both nationally and internationally,” she says. “The corporate sector will find it more difficult to recruit and retain the best employees. In the long term, it jeopardises the future recruitment of skills. It increases the risk of brain drain, of people being deported due to bureaucratic errors and of reduced competitiveness for Sweden as a knowledge and research nation.”

“Possible that interpretation of the law will be revised”

According to SDF’s calculations, between 2,000 and 5,000 doctoral candidates and young researchers are directly affected by the change in the law, depending on how many of them wish to stay in Sweden.

Jennifer Emsfors explains that the Doctoral Candidate Association believes that it is important that efforts to change the law and its application are made at different levels at the same time. “Universities and colleges need to get involved and take a stand. SULF and the Doctoral Candidate Association are working intensively on various fronts to bring about change. It is also vital that there is engagement from grassroots movements and individuals. It is possible that the Swedish Migration Agency’s interpretation of the law will be revised.”

“The requirement of at least 18 months’ employment is impossible for doctoral candidates to fulfil,” she continues. “Temporary employment is the norm for them. The Government and the Parliament can pass new measures, the interpretation of the law can be changed. Politicians can solve this if only the will to do so exists.”

Wants Sweden to be competitive

Jeffery Marker is a doctoral candidate in ecology at Karlstad University and a member of the SDF board. He is originally from the USA, but he is not personally affected by the changes in the law because he is a Swedish citizen.

“My friends and colleagues are concerned,” he says, “so that motivates me to get involved in this issue. It affects me emotionally. It affects my work and my colleagues. I want the people I work with and people I will work with in the future to be looked after. That’s important to me.”

“Sweden is my home country now, and I want it to continue to be competitive in order to attract doctoral candidates and researchers. What’s happening now threatens the competitiveness I, as a researcher myself, want Sweden to enjoy.”